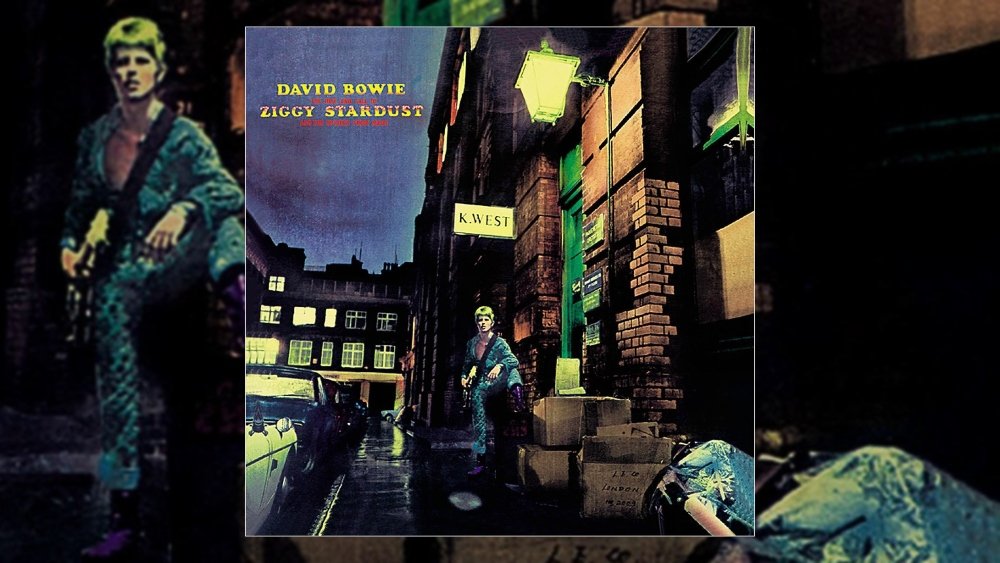

Happy 50th Anniversary to David Bowie’s fifth studio album The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars, originally released June 16, 1972.

Don’t fake it, baby, lay the real thing on me!

What is real, anyway?

David Bowie faked it so real, he was beyond fake.

Sure, several years before The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars dropped, the rock world had seen some of its brightest stars take on alter egos. The recent 55th Anniversary of the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band being a prime example. 50 years ago, David Bowie began taking this musical mask-wearing task to wonderfully strange new heights. He may be the first to use such shifting character inhabitations as a personal launch pad to rock stardom.

Born David Robert Jones in 1947, music industry politics, coupled with boredom, led him to abandon his birth name professionally by 1967. Appreciating the spike of Mick Jagger’s surname, Bowie redubbed his own after a fixed-blade fighting knife designed by the American pioneer and fighting frontiersman (Jim Bowie). Bowie’s blade proved long, sharp and powerful enough to deeply penetrate popular culture, while peeling back layers of persona like an onion. 1971’s Hunky Dory was Bowie’s first fully realized body of work. Ziggy Stardust was his earliest whole new skin unsheathed.

Whether or not Ziggy Stardust is Bowie’s greatest album is a subject for debate. It being the most important one, setting the stage for his legendary career, is not. It just is. Bowie famously told Melody Maker six months prior to its release, "I'm going to be huge, and it's quite frightening in a way. Because I know that when I reach my peak, and it's time for me to be brought down, it will be with a bump." Prescient words, spoken matter-of-factly, by a man who in the mainstream had barely made a dent, with exactly one UK pop hit (“Space Oddity”) and zero US Top 40 Billboard singles up until that point.

“Space Oddity,” released two weeks before Apollo 11’s July 24, 1969 landing on the moon, signified Bowie’s first step. But his mission to Mars on June 16, 1972, was the giant leap. Ziggy Stardust, and its subsequent tour, were transformational enough stateside, artistically and commercially, that it led to his record company re-releasing “Space Oddity” in 1973, watching that peculiarly now-iconic single float inside the Top 20 that April. Two months after “Space Oddity” peaked, the next Bowie single to streak up the charts was, fairly appropriately, “Life on Mars?” (#3 UK pop, #12 US rock).

What can I tell you about David Bowie, that he, or we, haven’t already said?

Despite his humble Brixton beginnings, unremarkable folkie debut, and preternaturally West End/Broadway theatrical leanings, Bowie the “cracked actor” proved on Ziggy Stardust that he “could play the wild mutation, as a rock-n-roll star.” After the dust settled, that transformation, to falling asleep at night as a rock & roll star, was complete, for the rest of his life.

Was Ziggy Stardust unexpected? Probably. Underappreciated? Perhaps, at least by the relative early ripple wake of its initial release, compared to its place among the rock canon today. Still, the album wasn’t borne into the world in a vacuum. This voyage into space began three years earlier. While the band who became the famed Spiders from Mars, with Bowie at the helm, began a “dry run” as an offshoot band called Arnold Corns, before recording sessions for Hunky Dory began in 1971. Three of the songs Arnold Corns recorded were “Lady Stardust,” “Hang On to Yourself” and “Moonage Daydream.” Each would appear in new versions with updated lyrics, among the eleven songs that ended up on Ziggy Stardust.

As a unit, the Spiders from Mars existed for an incredibly impactful but remarkably brief period, much like the fictitious band of the album’s narrative. The official lineup was set into place in 1971, when Trevor (Uriah Heep) Bolder was brought onboard to replace longtime Bowie producer Tony Visconti on bass. The Spiders’ drummer Mick “Woody” Woodmansey had been playing drums on each Bowie album since 1970’s The Man Who Sold the World. Together, these two formed the formidable rhythm section that gets prominent mention in the title track, “jamming good, with Weird and Gilly.”

Then, there was the guitarist, Mick “Ronno” Ronson. Boy, could he play guitar. Probably one of the most underrated Guitar Gods to ever visit earth. We’re talking “photon guns shooting out of his axe, with comet trails following behind” levels of wizardry. Even in 2022, we still have yet to hear a tone quite like Ronson’s from the ‘freak-out…far-out’ closing portion of “Moonage Daydream.” One can only imagine what that noise must have represented to listeners’ ears back in 1972. An extraterrestrial ambulance is my best guess. In fact, it still sounds like that to me.

Bowie, whose eye for talented co-conspirators is well-documented, played with a slew of great guitarists after he “had to break up the band” in 1974: Earl Slick, Carlos Alomar, Robert Fripp, Adrian Belew, Peter Frampton, Nile Rodgers, and Reeves Gabrels. And yes, he even famously featured the first recordings of a Texas blues-guitar gunslinger named Stevie Ray Vaughan on the Let’s Dance (1983) album. Yet, no guitar hero before or since the Spiders from Mars was ever more crucial or closely associated with Bowie’s oeuvre than Mick Ronson.

As Bowie recalled in a 1994 interview, a year after Ronson had succumbed to liver cancer, and twenty-three years before Bowie would perish from the very same disease: “Mick was the perfect foil for the Ziggy character. He was very much a salt-of-the-earth type, the blunt northerner with a defiantly masculine personality, so that what you got was the old-fashioned Yin and Yang thing. As a rock duo, I thought we were every bit as good as Mick and Keith or Axl and Slash. Ziggy and Mick were the personification of that rock n roll dualism.”

Agreed. For a good example of this dualism on full display, peep “Jean Genie” on NBC’s The Midnight Special in 1973, or witness Mick get far out on “Moonage Daydream” from the motion picture Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars, at one point needing to be reeled back in by a roadie, as the freaked out among the crowd attempt to hold onto Ronno, all the while barely hanging on to themselves.

The band name came from a mass UFO sighting that occurred in a Florence, Italy soccer stadium in 1954. Two rival Italian soccer clubs were mid-game when a group of UFOs, traveling at high speed, abruptly stopped over the stadium. The stadium became silent as the crowd of around 10,000 spectators witnessed the event, and described the UFOs as cigar shaped. It was later suggested that the most likely explanation for this phenomenon was that the silk of large mass migrating spiders had accumulated somewhere high in the atmosphere. I’m not sure which story sounds more unlikely, nor can I call it since I wasn’t there. But it’s the kind of extraordinary episode that likely would weave a wondrous web in the imagination of an artist, looking high above his own human station for inspiration. David Bowie combined both, and dubbed his gang of four The Spiders from Mars.

The album’s concept is almost purposefully vague. The protagonist Ziggy Stardust is an alien currently manifesting in human form as a bisexual, drug-addled rock star, attempting to present a message of peace and love to humanity in its last “Five Years” of earth’s existence. Yes, typing that narrative out just now in pitch form, it sounds ridiculous. Dafter than a deaf, dumb, blind pinball champion? Possibly maybe. Either that, or it’s six of one, half a dozen of the other. In both cases, it’s sold on the strength of its songs and the full commitment of its creators.

Unlike Tommy, a double-length rock “opera” in the more traditional sense, replete with overtures and call-backs, Ziggy Stardust puts its ray-gun to your head, just with straight-up joints. Eleven of them. 38 minutes and 29 seconds worth. All killer, no filler. It’s wild to realize that Ziggy Stardust is a minute-and-a-half shorter than Nas’ 1994 debut Illmatic, which decades later, became the standard for the great “short” album to a new generation of music fans. And like that “half-short, twice-strong” classic, Ziggy boasted no major hits.

The lead single “Starman” was its only Billboard charter, at a modest #65. Yet over forty years after that, the song was still reaching new audiences and blowing their minds. In 2015, it surfaced on the big screen, in one of the more memorable scenes from The Martian. How does Ziggy cram so many things, to store everything in there? “It Ain’t Easy.” Time takes a cigarette, puts it in your mouth. Even songs that didn’t make the album’s final cut, might be considered many lesser artists’ greatest work(s): “John, I’m Only Dancing,” “All the Young Dudes,” “The Jean Genie,” and “Velvet Goldmine,” to name some of those that would subsequently show up down the road.

The ones that remained reveal Bowie’s breadth of talent, plus an uncanny ability to seamlessly cross-pollinate genres with skillful songwriting. “Soul Love” is at first purely a sweet pop confection, with soul-infused accompaniment via Bowie’s alto-saxophone, a skill developed pursuing his childhood musical dream: to be the sax player in Little Richard’s band. But the lyrics, opening with a mother at her son’s grave, speak of the futility and anguish love can cause. “Lady Stardust” is a torch song, sung by a man who publicly declared himself gay, long before it was socially acceptable, even among the rock & roll rebel crowd. It became clearer later on that this stance was a bit put-on and intended to provoke. But to a marginalized gay audience around the globe and all the adolescents still figuring out for themselves, Bowie owning it without apology made him a lifelong ally.

Before the album’s character meets a tragic end as a “Rock ‘n’ Roll Suicide,” the song and show closer in this era, the Spiders go out guns blazing. Ronson’s fuzzy riffing take on rockabilly makes “Hang On to Yourself” a proto-punk classic. That’s immediately followed by two classic-rock radio nuggets that somehow never get stale in “Ziggy Stardust” and “Suffragette City.”

The sum total adds up to The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars being a masterstroke, by one of the greatest artists the genre ever produced. Bowie went on to make many more long players, including his final effort Blackstar (2016), released on January 8, 2016, just two days before his death. But do yourself a favor today. 50 years later, start Ziggy Stardust at “Five Years” and just let it play.

Enjoyed this article? Read more about David Bowie here:

Young Americans (1975) | Low (1977) | Earthling (1996) | Heathen (2002)

LISTEN:

Editor's note: this anniversary tribute was originally published in 2017 and has since been edited for accuracy and timeliness.