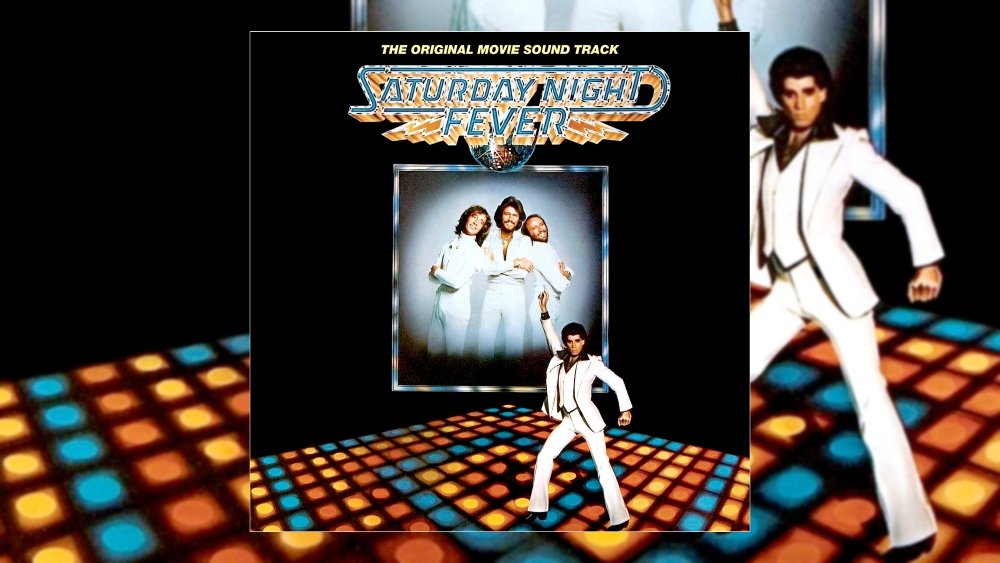

Happy 45th Anniversary to the Saturday Night Fever soundtrack, originally released November 15, 1977.

It might surprise some that the Saturday Night Fever soundtrack's inception happened rather unassumingly in an eighteenth-century estate in the French countryside, well over three thousand miles away from the Brooklyn streets with which it became synonymous.

The historic Château d'Hérouville, which was painted by Vincent Van Gogh in the summer of 1890 shortly before his death and was reportedly a residence of Frédéric Chopin, was eventually converted into a recording studio in the early 1970s. Elton John was among the first notable pop musicians who crafted an album there—fittingly dubbed Honky Château. Uriah Heep, Iggy Pop, Marvin Gaye, Fleetwood Mac, and Cat Stevens would follow suit at different points throughout the decade.

The Bee Gees, along with their co-producers Albhy Galuten and Karl Richardson and band members Dennis Bryon (drums), Alan Kendall (guitar), and Blue Weaver (keyboards), found themselves in Hérouville in early 1977 to mix their forthcoming concert album, Here at Last...Bee Gees...Live, which they'd recorded at The Forum in Los Angeles in December 1976. The temporary exile from their home base in Miami was purely financial—recording and producing in France provided a respite from the swelling tax rates in the United States.

The Gibbs were enjoying a return to commercial favor after a notable dry spell in the early 1970s. Their 1975 album Main Course and 1976's Children of the World were progressive explorations of the group's long-term affection for R&B music that would reignite both public and critical interest in their catalog. By this time, they'd scored two number one singles in the US with the perpetually infectious "Jive Talkin,'" and the urgently rhythmic "You Should Be Dancing,” plus a stack of other hits that included the Stylistics-influenced "Love So Right” and the phenomenally pungent "Nights on Broadway."

Also in play was the novelty of Barry Gibb's falsetto voice, which made its first appearance through the encouragement of veteran producer Arif Mardin during the sessions for Main Course. What began as a fascinating contrast to the Gibbs' already sterling harmonic blend soon became the primary vehicle for the band's music over the next year.

The Gibb-Galuten-Richardson conglomerate began work on what was planned to be the next Bee Gees studio album in early 1977 during their residence at the Château. According to Galuten, the overall vibe was one of assurance that they could capably build on the success they'd earned with the past two records. "You know, I had never known failure, and Karl as a producer had never known failure," he explained to me on the phone from his home in Los Angeles. "So 'You Should Be Dancing' and the success of that stuff—we knew that we had access, and we knew that we had a following, and we knew that the possibility for commercial success was there."

What they likely didn't know is that those sessions would not only add to the Bee Gees' lengthening string of hits, they would incite a musical and cultural revolution.

The Gibbs' longtime manager, RSO Records founder Robert Stigwood, reportedly interrupted progress on the new album with news of his decision to produce a film based on British music columnist Nik Cohn's July 1976 New York Magazine article, "Tribal Rites of the New Saturday Night." Considered at the time to be a truthful, informed examination of the rise of life and music inside disco clubs in the working-class neighborhoods of Brooklyn (he later admitted the work was fiction), the characters illustrated in Cohn's piece had compelled Stigwood to commit to telling their stories on screen.

He then asked his protégés if they would kindly scrap their project and contribute some of their newly-minted songs to the film's soundtrack. Galuten affirms that much of what appeared on the final cut of the Saturday Night Fever album was already written by the time Stigwood reached them. "Yeah, we had no idea about the film. We'd never seen it and we didn't know much about it at all. We weren't writing stuff for a film. We were just writing nice music that happened to work for the film. My memory is that they had roughly written the outline of 'Stayin' Alive" when they were in Bermuda with Robert before that, and they had the outlines of a lot of the songs [when they were in France]."

The pulse of the Saturday Night Fever soundtrack—and the film, for that matter—was really driven by just five songs: the Bee Gees' own original contributions of "Stayin' Alive,” "How Deep Is Your Love,” "Night Fever,” and "More Than A Woman," and Yvonne Elliman's "If I Can't Have You," which was also one of their compositions.

"Stayin' Alive" is probably the most iconic of the bunch, and certainly the image of Tony Manero's bravado-soaked strut in perfect sync with the song's opening bars has become one of cinema's most enduring sketches. On its own, it's a remarkable pop record that creates a wonderful paradox between the extreme reaches of Barry's falsetto lead and its grittier underlying message of survival in the streets. The Bee Gees' harmonies and the swirls of horns and strings ring like a perpetual chorus of chimes.

Underneath the layers of instruments and voices is a mechanically steady, almost chunky beat that drives the track forward. While you're hearing a real snare from the kit of the band's drummer, Dennis Bryon, the nearly-perfect punches are, in fact, a loop. Creating that specific element to sound machine-like was, ironically, a rather human-intensive process.

"The origin of that is...when I went to Berklee [College of Music] in Boston, we listened to a bunch of different music," Galuten recalls. "And there was a piece by Steve Reich called 'Come Out' that had originally been written as a result of the [Little] Fruit Stand Riot in Harlem. A woman had been shot, and a bunch of kids had been arrested, and there were protests. At any rate, he had samples of the kids talking and there was one phrase 'so the blood could come out', or something. And he looped it, and I remember it changing over the loop, but it repeated. And I always remember that. It would have been in '68 or something when I heard it.

And so when we were at Château d'Hérouville, Dennis' father had a heart attack, if I remember. But anyway his father was ill and he had to go back to the UK to see his dad in the hospital. And there was an organ there, something like a Hammond L100 with an awful drum machine. It just sounded and felt awful, you know, like drum machines were. That was even before the LinnDrum, so drum machines were really awful. So I said 'why don't we take a bar out of 'Night Fever' and make a loop out of it and we can vari-speed it to the right tempo?' And Karl said 'I think I can figure out how to do that.' Barry, Karl, and I sat and listened to 'Night Fever'—just the drums—and we found a bar that we thought felt really good and was kind of the right feel.

Karl made a copy of it onto a two-track and made a loop out of it. The loop went around the tape machine and over. He had the supply reel taped down so it wouldn't spin and the capstans were still connected. And it went over a mic stand—a boom mike, so a horizontal bar—and then hanging off of that was a seven-inch plastic reel just for ballast. So the tape just went around and around and around. And so we put that on, and we always thought we'd just replace it with real drums once we were done. But what happened was that the feel was so incredible after we got the instruments on, we were like, 'we can't take this off.' Nobody realized before that how great loops could feel. Obviously now, people use loops for everything because drum machines feel stiff."

That same innovation was used on recordings produced by the Gibb-Galuten-Richardson team for some time to come. "We used it on 'More Than a Woman,’ and eventually we used it slowed way down on 'Woman in Love' for Barbra Streisand. And on ['Stayin' Alive'] in particular was the first time we were really putting things together one at a time, unfortunately. I think now everybody does everything one at a time and I think we suffer a great loss for that because there's not enough people playing together in a room, which creates a lot of serendipity and interesting stuff that you don't get when it's all pieced out."

The opening guitar riff of “Stayin’ Alive,” reportedly modeled after Betty Wright's 1972 R&B classic "Clean Up Woman", has its own story, as do some of the other intricacies of the song's production. "The guitar part is something that I came up with on the floor when they were writing the song," Galuten confirms. "They were just sitting around and Barry was playing guitar and they were playing with lyrics and melodies, adjusting the song. And I was there with an acoustic and just came up with that, you know, (mimicking the opening guitar line) 'dah, dah, dah, dah, dah, dah-dah-dah.' So when we overdubbed, I taught that to Alan [Kendall], and we would punch everything in in little sections. He'd play that guitar part and we'd punch it in all of the sections that had it. And then we figured out amongst the three of us—I think Barry had some good ideas around the B-flat chord, the other section—and then we'd punch those in and out.

And with Maurice, the bass was not a typical Maurice Gibb bass line. So if you listen to the bass line for 'You Should Be Dancing,’ that's very much Maurice Gibb, which comes out of more like the British Invasion and not so much out of soul music that, for some reason, Barry and I were so enamored with. So the bass line is a case of, again, me sort of teaching Maurice this line that came out of my R&B roots and punching it in section by section. Barry was always very critical about the meter and getting the bass part right.

And Blue [Weaver] played the piano—it was a blues piano part. The strings were kind of collective, even though I did the orchestration and the conducting. I think a lot of the ideas were Barry's, the (mimicking the string lines during the bridge) 'dah, doo-doo, dah, doo-doo, dah-doo doo.' And the (mimicking the string lines leading back into the verse) 'eeeee-uh, eeeee-uh', you know, those slide things, was Robin's, if I remember."

Watch the Official Videos (Playlist):

Galuten also points out that "Stayin' Alive" was nearly botched mid-production because of interference from the film's producers. "They didn't originally know they were going to use it in the [film's] opening. They were going to use it in the dance scene in the middle. And they were going to have this montage in the middle, so they asked us to put together a break in the [song] for this ballad-y thing.

And [Barry, Robin, and Maurice] wrote it and we put it in. And we hated it. We said 'no, this can't be.' And I guess maybe that's part of the stimulus that made them say 'okay, well let's use this song for the opening credits instead.' And it's a credit to our confidence, you know? If we were less sure of ourselves, we might have said 'well, okay. I guess they know!' We were, like, 'no! This sucks! You had a hit song and you just blew it!' But of course, we didn't think like filmmakers. We thought like record-makers. We knew what a hit record was. We'd listened to pop radio and said 'this is a hit record now. If you change this, it's not.'"

The team's instincts were flawless. "Stayin' Alive" became one of the Bee Gees' most successful tracks.

The mellifluous ballad "How Deep Is Your Love" served as Saturday Night Fever's lead single. While there's strength in its sensitivity and warmth, its breezy sway between major and minor-chord expressions gives it a decidedly R&B lilt. Aside from Barry's outstanding natural-voiced tenor, which is at a peak level of clarity and deliberativeness here, Blue Weaver's complex Fender Rhodes flourishes and Galuten's sweeping string arrangement are the shining gems. It's certainly among the Gibbs' finest compositions.

A bootleg recording exists online of the brothers working out the song's chord structure on the piano with Blue Weaver, and it's interesting to hear them collectively resolve the song's melodic movement. At that formative stage, you can hear the three Gibbs in different combinations singing key phrases from the finished product, but most of the vocals are scatting. The song was eventually put on tape in a more finished form with Galuten. "I remember we did a demo of 'How Deep Is Your Love' and it was so good that even when we did the final mix we still went back to listen to the demo, because we weren't sure we'd beaten it."

Given that writing "How Deep Is Your Love" was such a collaborative, layered, time-intensive experience, it made a copyright lawsuit brought by part-time musician and composer Ron Selle against the Gibbs in 1984 seem improbable. Selle accused Barry, Robin, and Maurice of plagiarizing a song he'd written in 1975 as both his earlier composition and "How Deep Is Your Love" contained two musically identical eight-bar passages. The presiding judge initially ruled in favor of Selle, but it was later overturned on appeal, citing Selle had no proof that the Bee Gees had access to his composition—although it had been copyrighted, it hadn't been made available for public consumption.

"Night Fever" was the third and final Bee Gees single to be released from Saturday Night Fever. The track allegedly inspired the film's official namesake (an early working title was simply Saturday Night) at the suggestion of the Gibbs to Robert Stigwood. The song itself is a masterful R&B stroll, with yet another landmark orchestral arrangement that was apparently conceived by keyboardist Blue Weaver. "'Night Fever' started off because Barry walked in one morning when I was trying to work out something," Weaver recalled in The Ultimate Biography of the Bee Gees: Tales of the Brothers Gibb. "I always wanted to do a disco version of "Theme from A Summer Place" by The Percy Faith Orchestra or something—it was a big hit in the Sixties. I was playing that, and Barry said, 'What was that?' And I said, 'Theme from A Summer Place', and Barry said, 'No, it wasn't'. It was new. Barry heard the idea—I was playing it on a string synthesizer and sang the riff over it."

There's been lengthy speculation about whether or not the Bee Gees' version of "More Than a Woman" was supposed to have been released as a fifth single from the soundtrack. Galuten clarifies that the version by soul quintet Tavares, which also appears on the album, was the only one intended to see the light of day as an extract. "There were meant to be three Bee Gees songs, and a song written for Yvonne Elliman, and a song written for Tavares. Yvonne Elliman's 'If I Can't Have You' and 'More Than a Woman' were both written as demos for other artists." Tavares would end up scoring a minor top forty hit in the US with their reading, and they'd end up sharing Album of the Year honors when the soundtrack won at the 1979 GRAMMY Awards. Not receiving a commercial release didn't stop the Bee Gees' recording from receiving a massive amount of airplay alongside their other singles from the soundtrack.

Yvonne Elliman's "If I Can't Have You" was the fifth and last single to be featured from Saturday Night Fever, and would eventually reach number one in the US in May 1978. It's an exceptionally good pop record, receiving stellar direction from Freddie Perren, a veteran musician and former member of the legendary Motown production team, The Corporation, who famously helmed The Jackson 5's astonishing initial string of hits. It's also an anomaly in terms of it being a composition handed to someone by the Gibbs themselves with no additional involvement by them or their co-producers—a formula that would not be typical of the many tracks they'd write for other artists from that point forward. The Bee Gees' prototype was relegated to the B-side of the "Stayin' Alive" single and eventually surfaced on their 1979 Greatest compilation.

The only other known Bee Gees song that was developed during the Fever sessions was the initially unreleased "Warm Ride.” Galuten insists that it was never intended to be included on the album. "We had heard from somewhere that Roger Daltrey was looking for a song. So I think they threw that together for [him], who ended up not liking it. It was never meant to be a song for them." Their rough demo of the song was eventually released in 2007 as part of an expanded version of Greatest, and on first listen there are striking similarities in both tempo and tone to "Night Fever." Although it was rejected by Daltrey, Graham Bonnet, Rare Earth, and Andy Gibb all recorded different versions of "Warm Ride" between 1978 and 1980.

"It's interesting, Barry has always found stimulus writing for other people," Galuten continues. "So even when they wrote 'To Love Somebody,’ in his mind he thought he was writing that for Otis Redding—thinking, you know, 'this would be a great song for Otis...' And by the way, it would be. Part of what happened later when we got into all of those things with Streisand, and Dionne Warwick, and Kenny Rogers, and Diana Ross, was that Barry liked to have somebody to write for. He liked to have a project—he wasn't just writing in a vacuum. There are some writers who say 'you know, I have to get up every morning...' Diane Warren is one of those, you know, '...I write for six hours and I just do it because I have to write.' And going back to Bach, I remember he once said 'I hope I never have to write a piece of music without it being commissioned first.' It was like, 'okay, please write this organ piece for something,' and he would just write it. Barry liked to have stuff to write for, so when Robert [Stigwood] would say 'write a theme song for Grease,' it would give [him] a focus to come up with something inventive and creative because he would then see his world through that lens. Or that world through his lens."

When both the Saturday Night Fever film and soundtrack became publicly available in late 1977, they created a perfect maniacal storm that hadn't been seen before – and arguably hasn't been seen in quite the same way since. The film was relatively low-budget (a bargain at just $3.5 million in production costs) with a generally unknown cast, save for John Travolta whose star had been rising steadily prior to his turn as Tony. Eventually, it would gross over $237 million in the US and become an unqualified success.

What was once considered a subculture—lives lived after dark in discos in a hazy mélange of music, drugs, sex, and alcohol—was now pushed forcibly into broad daylight by the film. The political and social implications of the 'disco' era are fascinating, and at times disheartening. The film delves frequently into deep trenches of racism, misogyny, homophobia, classism—not to mention how plainly it contends with sexual violence. While most of American culture in the 1970s—including the film—has been dismissed in later years as comedic blather, there are incredible complexities that probably require a dissertation to explore rather than an album retrospective.

The soundtrack's commercial impact is utterly staggering. To date, Saturday Night Fever has sold in excess of 50 million copies. In the first half of 1978 alone, the Bee Gees' sole contributions to the Saturday Night Fever soundtrack logged 14 weeks at number one on the Billboard Hot 100 singles charts in the US. If you add the singles that were either penned by them and/or produced by them that also reached number one in the same period, that total extends to 19 out of 26 weeks. In March, the Bee Gees would achieve something only the Beatles had managed to previously by having five of their songs chart in Billboard's top ten simultaneously.

The Gibbs essentially spent most of the year competing with their own material because virtually no other artist was able to match their accomplishments. Consider this unbelievable sequence of events: "How Deep Is Your Love" reached number one on December 24, 1977 for three weeks. On February 4, 1978, after a brief reprieve provided by RSO stablemates Player and their signature ballad "Baby Come Back,” "Stayin' Alive" claimed the pole position and remained there for four weeks, only to be unseated by Andy Gibb's "(Love Is) Thicker Than Water." When his single fell off, it was immediately replaced by "Night Fever", which remained at number one for eight straight weeks. When that was finished, Yvonne Elliman's recording of the Gibbs' "If I Can't Have You" was at the summit. Just over a month later, Andy would score another seven weeks at number one with "Shadow Dancing." By year's end, the Barry Gibb-penned, Frankie Valli-sung "Grease" would also spend two weeks at the top. Two more Andy Gibb singles, "An Everlasting Love" and "(Our Love) Don't Throw It All Away", plus "Emotion,” which Barry and Robin had written for Australian artist Samantha Sang, would also reach the top ten.

The balance of the soundtrack album is comprised of original score pieces commissioned by American composer David Shire, in addition to an arsenal of mostly familiar tracks like The Trammps' "Disco Inferno" and Kool and the Gang's "Open Sesame" that were chart hits within the past two years. The artists probably benefited from the additional exposure in the film and on the soundtrack, but it's likely they didn't reap the rewards of the album's explosive sales. "In the annals of history, it could be one of the most profitable records ever created," Galuten insists. "Because it's a double album, and I don't know how much Robert paid David Shire in royalties, because a lot of the songs like 'Night On Disco Mountain' are just sort of orchestra stuff to fill out the album. I mean, you know, he did a good job and they're all fine and lovely, but they're not pop songs. And songs like KC and the Sunshine Band's 'Boogie Shoes'—it was all in the plan to have a few hits and to have a lot of stuff that was inexpensive. I believe I heard that [Stigwood] has licensed those songs, like the Ralph MacDonald track ['Calypso Breakdown']...for pennies.

I think the only things he was paying full royalties on were the major artists. I don't even know what the deals were like for Tavares or Yvonne Elliman. They didn't have huge hits at the time, so they probably had really low licensing fees. The person that made out like a bandit with that record, besides the Bee Gees because writers' royalties are fixed and they're not negotiable, was Robert and RSO Records."

When asked when he believes he realized that the songs he helped to create for Saturday Night Fever had become much more than just a stack of hit records, Galuten insists he had a hunch from the beginning that they were special. "These songs were so good, and we were all so focused. Because there was nothing else going on in France—we didn't know anybody there, it was out in the middle of the country. We'd get up in the morning and go to the studio and hang out all day long. There was nothing else to do. We knew that these were amazing. There was just the sense that, like, 'oh my God. These are absolute smashes.'

When you hear a phrase like 'Night Fever' and you go 'no-one has ever said the phrase 'Night Fever' before,' or associating the image of 'Stayin' Alive' with the streets of New York and daily life and...it's not about the Vietnam War, you go 'oh my God.' Barry had this knack for—you could call it hyperbole—but this brilliant sort of mapping of these extreme adjectives onto things that might otherwise be mundane. And it gives you perspective to see them as being important."

While the Bee Gees' music was ubiquitous throughout most of 1978, they made few public appearances and scheduled no live dates in support of Saturday Night Fever. In March 1978, right in at the pinnacle of their chart-breaking halcyon, they retreated back into the studio to begin work on what would eventually be the Spirits Having Flown album. When asked if the team was at all nervous to record a commercially successful follow-up to their Fever contributions, Galuten insists they weren't. "I think we were protected by the hubris of youth. When we were working on songs, we weren't wondering 'I wonder if this is a hit?' We would take bets on how many weeks at number one it would get. So to answer your question about us being nervous going back into the studio: no. We were on fire."

Public favor of Saturday Night Fever's music and, by association, the Bee Gees' popularity, has waxed and waned at different points over the years. Although perhaps no rejection of either was as caustic as the "Disco Demolition Night" baseball promotion at Comiskey Park in Chicago in July 1979, during which local radio station WLUP-FM offered 98 cent tickets to a Chicago White Sox-Detroit Tigers double-header in exchange for fans bringing their disco records to the stadium to be destroyed in an on-field explosion. It was nothing short of riotous, leaving many to speculate if the lambaste was really about the music or the cultural and social identities from which the music was appropriated. The Gibbs themselves, frustrated by the backlash they'd residually receive throughout the 1980s, have also dismissed their involvement with Fever at different points. When asked about "Stayin' Alive" by Rolling Stone in 1988, they quipped "we'd like to dress it up in a white suit and set it on fire."

But yet, great music is perennial (and yes, I consider the Bee Gees' contributions to the soundtrack to be indisputably great) and nostalgia seems to be working more for the music of Saturday Night Fever these days than against. Galuten believes the soundtrack and the film still have something profound to offer forty-five years later. "[It's] about how people...the music that influences them is what they listened to in high school and college. And when you're 30, 40, 50, 60, the music from your teenage years has an impact on you viscerally and emotionally that no later music ever has. If you talk to anybody and ask them what their favorite music is, across ages, the similarity itself is not the music. It's the age they were when the music was popular. So all the people that were growing up at this time—this was very important to them.

The thing that makes music really touch lots of people is when it gives some sort of a voice to people who have not had a voice. The Beatles gave a voice to adolescents, and obviously Motown and Stax gave a voice to people who did not have a voice, just like hip-hop did. And so I always wonder 'who did Saturday Night Fever give voice to?' And then I realize it was working-class Americans who had no output and nobody representing them. And here was something saying 'even though my day-to-day life may be mundane, I can go out on Saturday night and I can resonate. This speaks to me.'"

LISTEN:

Editor's note: this anniversary tribute was originally published in 2017 and has since been edited for accuracy and timeliness.