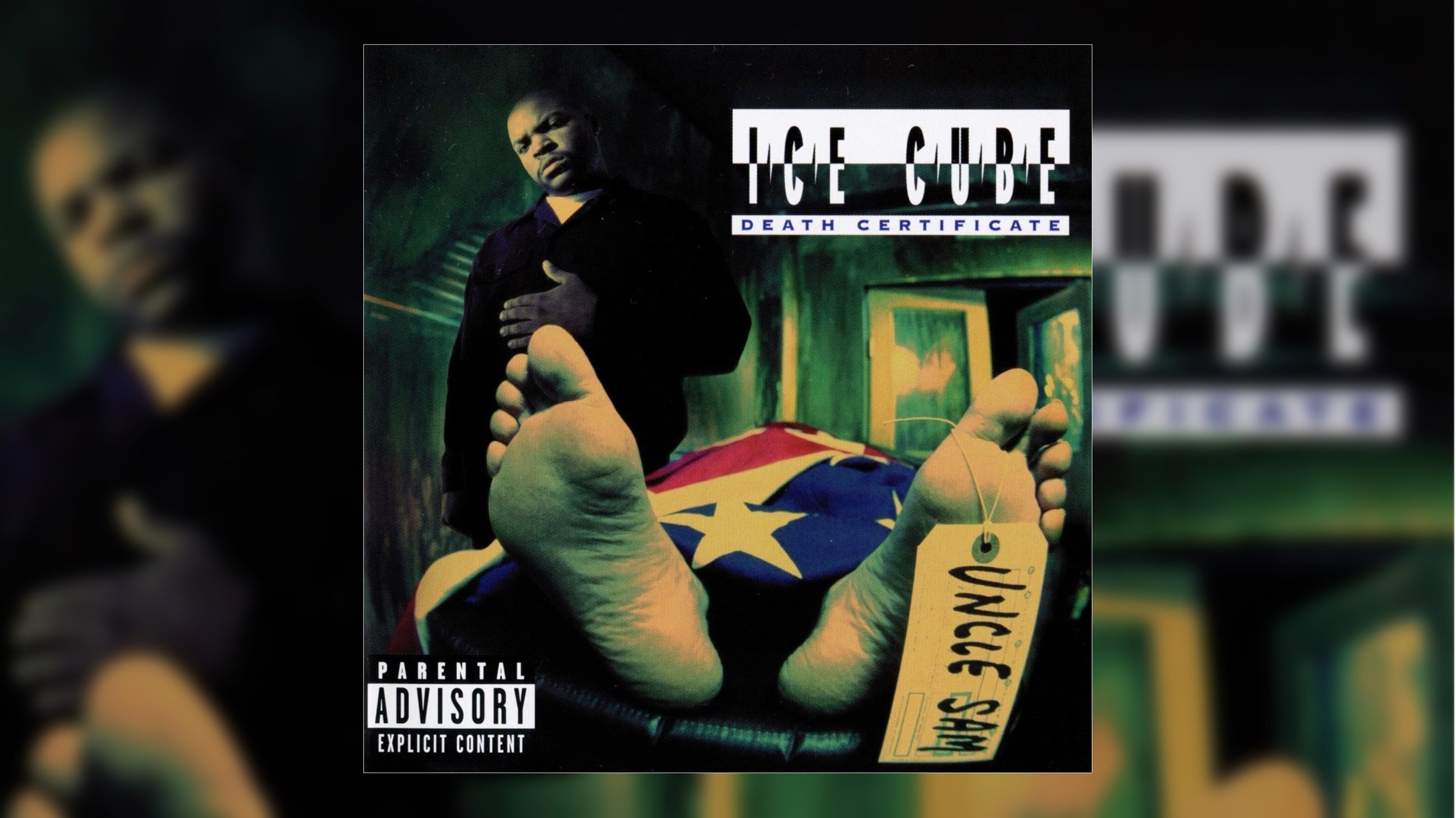

Happy 30th Anniversary to Ice Cube’s second studio album Death Certificate, originally released October 29, 1991.

Anger can be a messy emotion. It’s hard to deal with. It’s over-powering. It can cloud judgment and make it difficult to focus. But when it’s harnessed correctly, it’s as potent as anything, especially in a musical setting. With Death Certificate, O’Shea Jackson a.k.a. Ice Cube created the definitive angry album, and its potency has not been diluted by 30 years of history

By the time Ice Cube recorded Death Certificate in 1991, he was enjoying rap superstardom. He was about a year and a half past leaving the definitive gangsta rap group N.W.A, against the recommendations of his record label, Priority Records, and the man who served as his mentor and collaborator, Chuck D of Public Enemy. With the release and the success of his first album AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted (1990) and the Kill At Will EP (1990), he had successfully forged his own identity as an acclaimed solo rapper that achieved considerable commercial success without securing radio play and compromising his content. The summer of ’91 saw the release of the John Singleton directed Boyz N The Hood, featuring Cube in a supporting role as the misunderstood Darrin "Doughboy" Baker, for which he even received some Oscar buzz.

Months earlier, N.W.A had released their own second album, Efil4zaggin, a critically acclaimed work, but one characterized by an almost cartoonish amount of over-the-top violence. With Death Certificate, Cube opted for a mix of gritty reality, absolute disdain for authority, and flashes of gallows humor.

He also sported a new sound. The Bomb Squad, the production crew best known for its production work with Public Enemy and much of AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted, was in the midst of a hiatus. So Ice Cube instead turned to Sir Jinx, who had also worked behind the boards for AmeriKKKa’s Most, as well as the Boogie Men (the legendary trio of DJ Pooh, Bobcat, and Rashad). As a result, the production favored traditional west coast funk and P-Funk samples, rather than the Bomb Squad’s wall of sound. Despite the absence of the Bomb Squad, the album’s beats and overall feel had a rougher, harder edge. Combined with Cube’s blunt-force lyrics, Death Certificate is one of the darkest, angriest albums ever recorded.

Full disclosure: Death Certificate is very much about the life experiences of young Black men during the early ’90s, and while I may have been young in the early ’90s, I am not a Black man. So while I do love this album, I don’t have the personal relationship and direct psychological connection to many of the issues that Ice Cube details throughout Death Certificate. While I can work to understand the context, I don’t presume to know the raw, emotional feelings behind its content.

Death Certificate is brimming with raw, emotional feeling. The album is famously separated into “Death” and “Life” sides, with the “Death” side representing “where we are today” and the “Life” side serving as a “vision of where we need to go.” Cube tackles more traditional street tales on the first half, while the second half is more overtly political. But both sides reflect a cold fury toward the living conditions of South Central Los Angeles. The anger bubbles beneath the surface on the first half of the album, but erupts in full force on the latter half.

Well, Ice Cube unleashes some of his overt wrath on the album’s opening track “Wrong Nigga to Fuck Wit,” the LP’s blistering mission statement. With the backing of a fast-paced Sir Jinx track, Cube dusts off the AK and reminds the listener that ain’t a damn thing changed but the year, and he’s still not be trifled with. He unloads a barrage at pop rap, New Jack Swing, and the Raiders (“Al Davis never paid us”). He saves a whole clip for LAPD Chief Daryl Gates, who he literally roasts into “Kentucky Fried Cracker.”

This album also solidified Ice Cube’s reputation as a masterful storyteller. Cube was extremely adept at providing his unique perspective on a situation, adding the narrative touches and details to make it seem even more real. “My Summer Vacation” is the best song in Cube’s extensive catalogue and one of the best story raps ever recorded. With the track, Cube addresses what was then the relatively new phenomenon of gangs relocating from Los Angeles to cities where gang-banging was only something they saw in Colors or heard on a rap album. The song predates the infamous HBO documentary Banging in Little Rock by a good three years.

On “My Summer Vacation” Cube vividly explains the process of moving the crack-slanging operation to St. Louis, finding a corner to set up shop, and then, “What do you know? A drive-by in Missouri.” After drafting the locals to join their gang set, things eventually go sour. Before Cube can abscond to Seattle, he gets arrested and finds himself staring at the horrors of incarceration and trying to maneuver around a double-life plea bargain. The description of aspiring gang-bangers “dying for a street that they never heard of” along with visions of faces full of tattooed tears sell the track’s authenticity.

A common theme across the album is an overall distrust of inefficient bureaucracies. There’s a palpable frustration towards agencies and institutions that are designed to help, but often fall appallingly short within the lower income Black communities, often failing the populations that need them the most. One example is “Alive on Arrival,” which details the extremely bleak outlook of South Central’s over-taxed public hospitals. Cube details surviving a drive-by shooting, only to end up in MLK Community Hospital, where death seems just as certain. He’s also forced to contend with LAPD officers more concerned with his potential gang affiliation than his bullet wounds.

“A Bird in the Hand,” the second best song Cube ever recorded, is essentially a thesis on why young Black men turn to selling drugs in their communities. Here Cube takes the role of recent high school grad and new father struggling to make ends meet and feed his family on a McDonald’s worker’s salary. Faced with inefficient social programs and a President who doesn’t bother to care about the plight of the Black community, he turns to selling crack as a more expedient way to put food on the table, and finds that he now has money to spare. The song illustrates the irony of a government that wouldn’t give the Black community living in the inner-cities the time of day when it comes to punching the clock and dead end jobs and struggling to make rent, but all of a sudden cares when members of these communities “stop filling out their W2s” in favor of dealing drugs.

Cube saves most of his venom for the United States government and white power structure. He begins tackling these entities with full force on the ‘Life” side of the album. “I Wanna Kill Sam” is his effective screed against historical white supremacy and the irreparable damage it has caused the Black population in the United States.

The track “Black Korea,” is, well, pretty racist in its own right, as Cube unloads on the Korean population of Los Angeles, particular Korean-owned markets located in economically depressed neighborhoods. It is worth noting that the song was written largely in response to the Latasha Harlins murder, a young Black teenager who was killed by a Korean storeowner in early 1991. Despite being convicted, the woman who shot Harlins later received an extremely lenient sentence from the judge in the case.

Cube then trades anger for palpable contempt on “True to the Game,” targeting three types of “sell-outs” that he views as betraying the Black community. He’s considerably less disdainful on “Color Blind,” the anti-violence posse cut. Rappers Threat, Kam, WC, Coolio, King Tee, and J-Dee, along with Cube, use the melancholy track to both empathize with young Black men who get caught up in gangs, while hopefully providing solutions on how to extricate themselves from the cycle of violence.

Though much of Death Certificate’s subject matter is unrelentingly grim, Cube knows when to inject some much needed humor. “Steady Mobbin’” is a relatively buoyant tale of Cube rolling through his hood, pondering how to come up without selling bean pies or bootleg t-shirts, while taking time to enjoy a soul food meal, and find a little female attention. “Look Who’s Burning” humorously explores the consequences of not practicing safe sex, with Cube advising people to protect themselves lest they end up like Heat Mizer.

But even on relatively carefree coming-of-age tales like “Doing Dumb Shit,” there’s a dark subtext, where Cube tells of going from days of playing “hide and go get it” to “beating punk fools with a baseball bat.” Though he explains how he was set straight by his parents, he laments the generation of youths that came after him who, without a similar support system, ended up dead instead.

The album draws to a close with “No Vaseline,” hands down the best dis track of all time. It was the logical conclusion of the beef that had been simmering since Cube left N.W.A, through disses on the group’s post-Cube recordings 100 Miles and Runnin’ & Efli4zaggin, to shots back on the Kill at Will EP to serious brawls with N.W.A cohorts Above the Law backstage at a concert in Anaheim and during the 1990 New Music Seminar. And with the opening ad-lib of “Oh yeah, it ain’t over motherfuckas,” Cube unleashes what quickly becomes an unending barrage of lyrical brutality.

Cube goes for the throat and does not let go, leaving damn near nothing untouched. He accuses N.W.A of forgetting their roots and turning their backs on the street. He implies that they were aping his style. He suggests the group’s manager Jerry Heller and Eazy-E were fucking them, figuratively and literally. He declares that Eazy sold out by attending a banquet with George Bush, Sr. It’s the musical version of Sonny Corleone vs. Carlo Rizzi (minus the blatantly missed punch). N.W.A was left collectively bleeding and broken in the street, while Cube strutted away without a scratch. I will say that personally, it was impossible for me to take N.W.A seriously as a group after this song surfaced. Soon after Death Certificate’s release, Dr. Dre left the group, ostensibly for the same reasons that Ice Cube bailed, and N.W.A, for all intents and purposes, broke up.

The raw, hardened anger of Death Certificate resonated with Cube’s audience. The album went double platinum, selling at least as many copies as N.W.A’s Efil4zaggin. Death Certificate is considered by many as Cube’s finest LPs (I personally have it barely a notch behind AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted) and one of the best hip-hop albums of all time (no argument here).

Three decades later, it’s hard to say if age has mellowed Ice Cube. Since his initial appearance in Boyz N The Hood, he has gravitated toward making films. There’s a whole generation of hip-hop fans who are more familiar with him as the star of the Barbershop, Friday, and Ride Along movies than for his career as a rapper. O’Shea Jackson, Jr. has opted to follow his father into the film part of the family business.

These days, Cube is mostly known for his sports endeavors, He reconciled with the Silver & Black years ago, and has become one of the team’s most prominent fans, following them back to Oakland and then to Las Vegas. He also spearheaded the Big3 Basketball League in 2017, which has persevered through the COVID-19 pandemic and is still in business,

However, Cube has continuously maintained in interviews that he stands by everything he said on Death Certificate, and told the Washington Post in 2015 "the only thing I regret now is not being as informed as I thought I was at the time I made the records.” In that same interview, he describes his songs from that era as time capsules, reflecting how he felt at that exact moment.

And in many ways, Death Certificate did precisely capture a moment in time in Los Angeles, where the Black population was reeling from years of gang violence, an indifferent and often hostile police force, and the overall feeling that in the eyes of many their lives had no value and did not matter. Less than a year later, the city would explode, making Death Certificate extremely prescient in that respect.

Now, two decades into the 21st century, it’s pretty striking how much things haven’t changed in the United States. We’re a little over a year removed from the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police officers, and the subsequent protests that erupted across the country in its wake. Too many other senseless killings of Black and Brown men and women at the hands of law enforcement, from Breonna Taylor to Manuel Ellis, continue to roil tensions in this country. So while deadly police brutality may be more frequently documented, it doesn’t appear to be abating any time soon.

Many rappers and crews from this generation have been documenting these troubling times through their music, working to capture the spirit of this particular moment in time. Still, none have been quite as incendiary as Death Certificate. The lessons that this album teaches and the warnings it gives are still applicable today.

LISTEN:

Editor's note: this anniversary tribute was originally published in 2016 and has since been edited for accuracy and timeliness.