Happy 30th Anniversary to Pulp’s fourth studio album His ‘N’ Hers, originally released April 18, 1994.

In the mid-90s, the UK was engaged in a ferocious Civil War, played out in the pubs, clubs and stadia the length and breadth of the nation. Hordes of swaggering, mutton-chopped northerners fueled by the Gallagher brothers’ brand of rehashed rock & roll excess raged against southern art school wannabees who reveled in the pseudo-intellectual tunesmithery of Damon Albarn’s Blur. The streets ran crimson with the blood of both sides—a nation divided, families torn apart.

This is, of course, total bollocks. (We’d have to wait till Brexit for that level of insanity.)

That might, however, be the impression you’d have if you’d read the tabloid papers at the time. Always happy to lie, exaggerate and create a problem where one doesn’t actually exist, they created the notion that you had to pick a side, despite the fact that the whole UK music scene was exploding with creativity, no matter the genre. Against this backdrop of partially fabricated internecine musical conflict, there rose a third way to approach the dilemma of choice.

Hailing from the steel city (Sheffield), Pulp offered people like me (who were way too uncool to feel any affinity for either of the two aforementioned major players) another option. Formed in the late 1970s by a teenage Jarvis Cocker, the early years consisted of lineup changes, abortive record deals and experiments with different sounds. All of which laid the perfect kind of foundation for the misfit music that adorned their magnificent 1994 album His ‘N’ Hers.

I’d love nothing more than to tell you I was an avid purchaser of the twin bastions of UK indie rock journalism, Melody Maker and the NME, but that would be the second load of bollocks in the space of a few paragraphs. I was in the midst of discovering and becoming addicted to all things Princely when songs from His ‘N’ Hers started to reach the pages of those hallowed mags. I couldn’t even tell you the circumstances under which I first heard Pulp, but I can tell you they should never have stood a chance with me.

But how did they manage to avert my gaze from all things purple?

The seeds of my attraction lay in my childhood. My granddad lived in Sheffield whilst we lived some 30 miles away in a pretty, semi-rural town in the Peak District. Most weekends involved a trip across the moors and a drop into the city but this wasn’t the bright, rejuvenated hipster-haven of today—this was the 1980s. Sheffield, like many other industrial parts of the country, was ravaged by attacks on traditional industries like coal mining and steel fabrication from a Conservative government that seemed hell bent on destroying society for the benefit of itself. It was grim (to my eyes at least).

Watch the Official Videos:

Run-down and plagued with graffiti and vacant lots, it was a totally different world to the one I lived in—each journey there scared and thrilled me in equal measure. Once in the warmth of my granddad’s home, the world outside faded from view, but all it took was a trip to the local park to bring the dangerously exhilarating realities of life in Sheffield flooding back. Loud, wild-eyed kids shouted with a cadence and tone that was completely alien to me, a sheltered boy from a quiet home.

In Pulp’s lyrics I found a reminder of those feelings of being a fish out of water. But, more importantly, they pulsed with the same seediness that thrilled me vicariously on those trips to the “big, bad city.” And pulsing described the music too—a surging, wanton energy coursed through the veins of the music, in perfect contrast to the self-deprecation, desperate pleas for love (and lust) and sordid details of ordinary, everyday lives that were contained within the lyrics.

Those responsible for this gloriously unseemly concoction were the five longest serving members in the band’s history: Russell Senior played guitar and violin, Candida Doyle played keys, Nick Banks was drums and percussion and Steve Mackey was on bass. And then, there was Jarvis Cocker. A man, all knees and elbows, whose wiry frame wore clothes so uncool and ill-fitting, you’d think they’d been borrowed from the deceased pensioner next door.

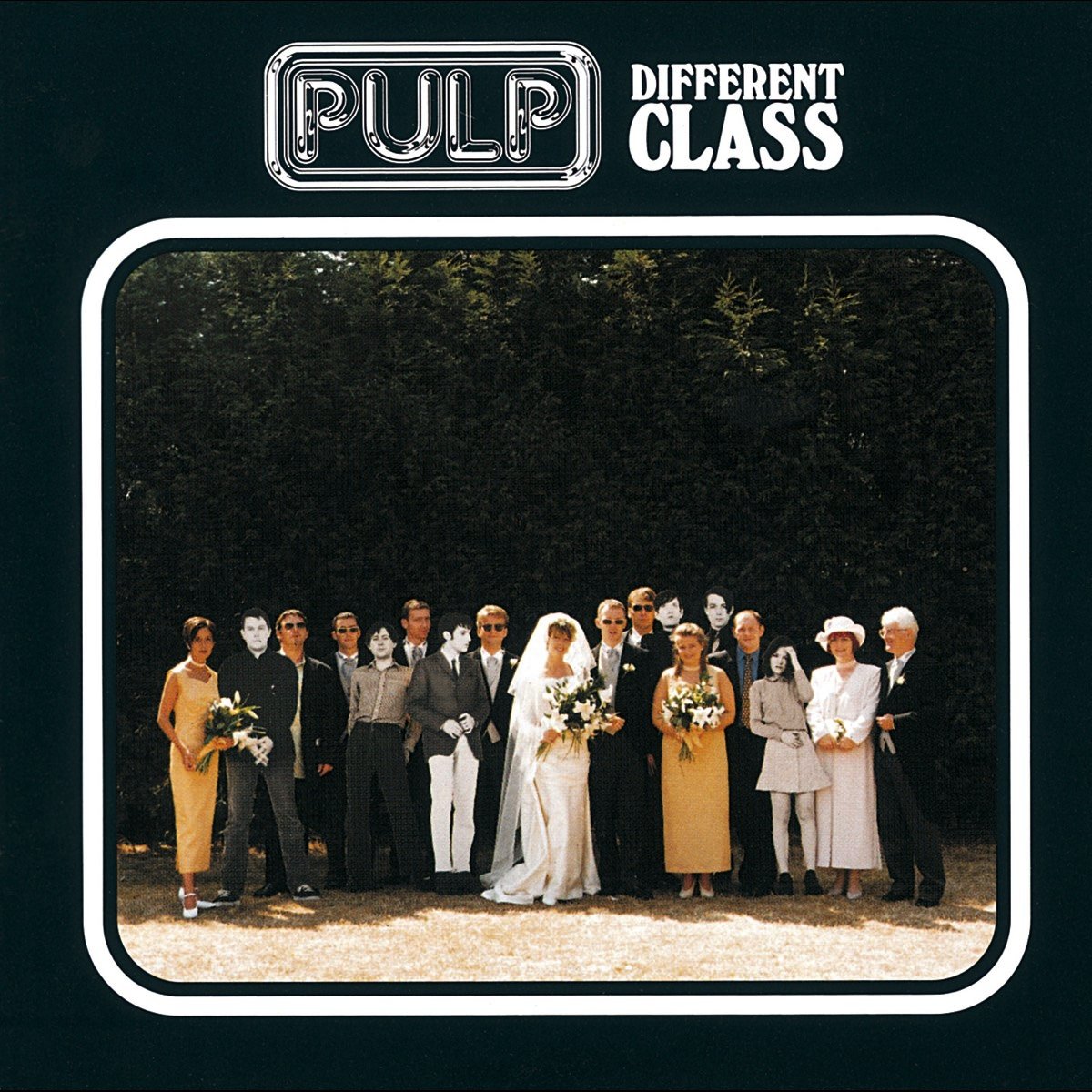

Yet this album thrust him towards the dizzy heights of national consciousness. His manic, jerky energy and louche delivery made a winning combination and propelled the group towards the tumultuous peak that their monstrously successful follow-up album (1995’s Different Class) scaled.

“Joyriders” does not hang about in setting the scene, both musically and lyrically. An immediate crunch of guitar goes hand in hand with a withering takedown of disaffected youth doing senseless things: “We can’t help it, we’re so thick we can’t think / Can’t think of anything but shit, sleep and drink.” That, however, is the end of any explicit social critique (in the largest sense). Instead, Cocker focuses his lyrics on illicit sexual encounters, the mundane minutiae of life and relationships, and “saving” mistreated women from the clutches of boorish, unimaginative men.

On the exhilarating “Lipgloss,” he bemoans the sacrifices of women in terrible, duplicitous relationships: “No wonder you’re looking thin, when all that you live on is lipgloss and cigarettes / And scraps at the end of the day when he’s given the rest to someone with long, black hair.”

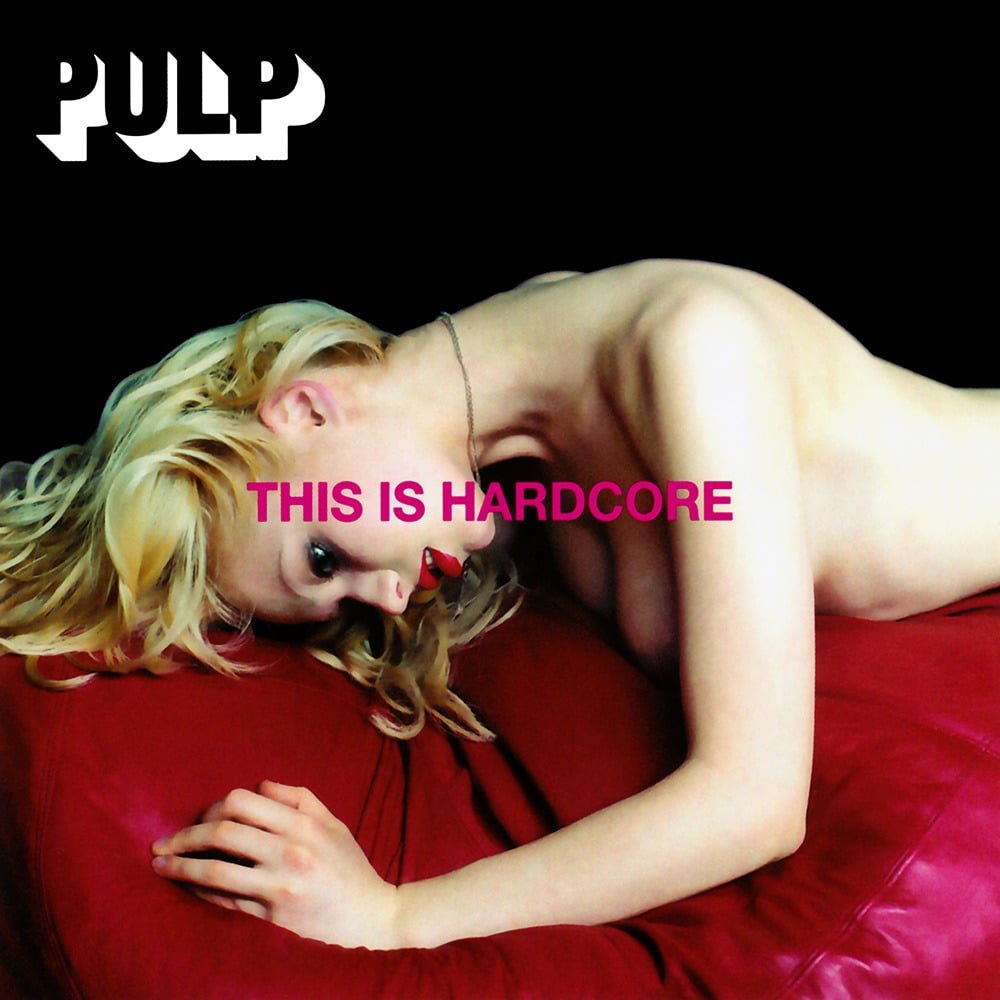

Enjoying this article? Click/tap on the album covers to explore more about Pulp:

The joy of Cocker’s lyrics lies in the simplicity of them—there are no hi-falutin’ words, no pretense—just profound, human details of tattered lives and torn hearts sung without irony or condescension. At other times, his desire gets the best of him and the singing is replaced by a half-spoken incantation of carnal voyeurism.

“Acrylic Afternoons,” “She’s A Lady,” and “Pink Glove” offer ample evidence of his under-the-counter charms. The Morse Code keyboard of “Acrylic Afternoons” gives way to Cocker’s unique breathy brand of seduction: “On a pink quilted eiderdown / I want to pull your knickers down / Net curtains blow slightly in the breeze / Lemonade light filtering thru the trees.” Pleading for a snatched piece of afternoon delight, he howls and leers like a wild beast.

“She’s A Lady” throbs with dancefloor drums and scything guitar lines while Cocker sings of obsession and regret as the clarion call of single keys rings out. “Pink Glove” simmers in seediness and is a fine example of Cocker’s desire to save women from disastrous relationships and position himself as the savior.

For all the magnificence of the album, two songs stand out like pole stars in the night sky. “Do You Remember The First Time” builds like a dance track breakdown, before reveling in the guitar driven chorus. In part about miserable sexual experiences, but also in part another entry in the canon of “saving” women from awful partners: “You say you’ve got to go home ‘cos he’s sitting on his own again this evening / I know you’re gonna let him bore your pants off again…Still you’ve bought a toy that can reach the places he never goes.”

Lurking in the middle of the album though, sits a song that means the world to me. A tale of teenage sexual exploits, “Babies” has an undeniable energy and vigor that contrasts with the hesitant, awkward lyrics to create something that mirrors those torment filled teenage years—bristling with confidence one second, laid low by paralyzing self-doubt the next. Like a kitchen-sink dramatist, Cocker mines the mundane everyday experiences for the details that resonate most with the audience: “Well it happened years ago, when you lived on Stanhope Road / We listened to your sister ‘cos she was two years older and had boys in her room.”

His ‘N’ Hers began a classic three-album arc of breakthrough–triumph–disaffection for the band that made them one of the key cultural forces of the 1990s in the UK. It is hardly surprising though that they failed to translate to the USA—they are a uniquely British phenomenon, too knowing and unpretentious to suffer the more foolish aspects of the US lightly.

The states’ loss was, undoubtedly, our gain.

LISTEN:

Editor's note: this anniversary tribute was originally published in 2019 and has since been edited for accuracy and timeliness.