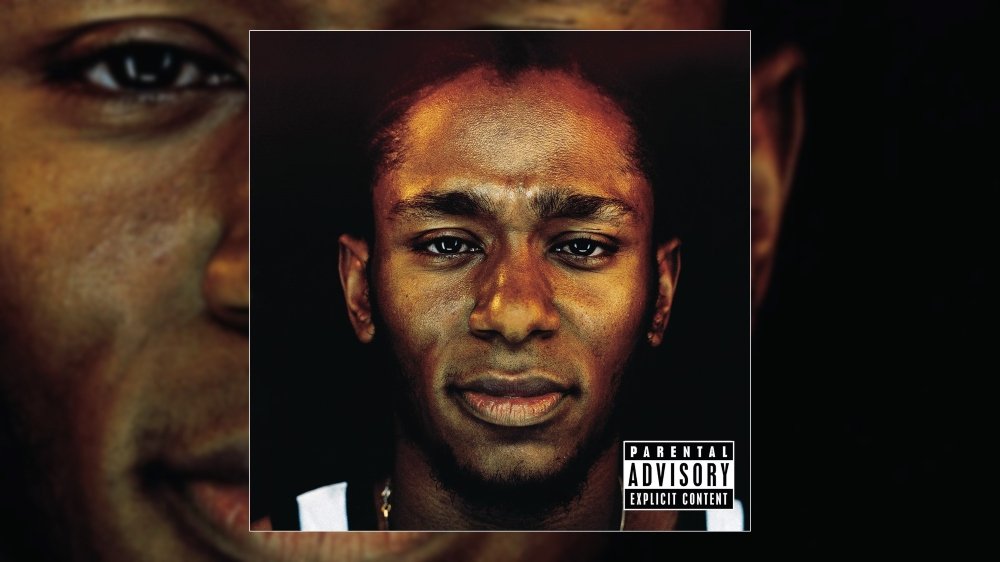

Happy 25th Anniversary to Mos Def’s debut solo album Black On Both Sides, originally released October 12, 1999.

“People talk about hip-hop like it's some giant living in the hillside, coming down to visit the townspeople. We are hip-hop.”

This statement, made by Dante “Mos Def” Smith (a.k.a. Yasiin Bey), perfectly illustrates how questions about the “state” of hip-hop are so often misguided. Mos Def speaks these words on “Fear Not Of Man,” the intro to Black On Both Sides, and they resonate as powerfully now as they did 25 years ago, when the album was first released.

He continues, “So the next time you ask yourself where hip-hop is going ask yourself: where am I going? How am I doing?” While Mos implores his audience to be proactive in helping hip-hop music put its best foot forward, he himself is ready to lead by example. With Black On Both Sides, his debut album, he decides to set trends rather than follow them.

Mos Def first began to attract a following in the mid ’90s as a member of Urban Thermo Dynamics, along with his brother and sister. As the decade progressed, the Brooklyn native made appearances on records by De La Soul and began establishing a presence in New York’s thriving underground scene. He soon became one of the cornerstones of Rawkus Records, a Manhattan-based independent label that was becoming synonymous with non-mainstream hip-hop. Mos eventually formed the hip-hop super duo Black Star with fellow BK resident Talib Kweli, and released their debut album Mos Def & Talib Kweli Are Black Star in 1998.

I’ve written before that during this period of time it appears that Mos Def was going to end up as one of the greatest hip-hop artists of all-time. He was not only a skilled emcee, but a skilled vocalist as well, capable of crooning melodic verses as well as he could deliver potent rhymes. He possessed the lyrical skills and limitless charisma. Black On Both Sides seemed to point to a trajectory where what he could achieve as an artist had no ceiling.

Black On Both Sides is a sprawling undertaking that matches Mos Def’s aspirations. Clocking in at over 70 minutes, it sometimes feels overlong and in need of focus, but when it’s on point, it’s better than many of the releases of its era. Mos Def does not lack for ambition. He tackles both the macro and micro, educating the listeners about global shortages while also chasing the fine shorty who lives up the block. His drive to create and inspire is impressive, and it resulted in an album that still holds up today.

Mos begins Black On Both Sides by speaking extensively about his love for the music. The Diamond D-produced “Hip-Hop” plays like a journal recounting the important components of the culture, each one integral to its development. He outlines the art form’s evolution, explaining how emcees can construct their rhymes, and breaking down the cyclical nature of popularity within the music. Mos also stresses how the music is not created in a vacuum, but rather it’s shaped by the environment in which it’s created.

Listen to the Album:

Meanwhile, “Love” is Mos’ love letter to the art of emceeing. Over a piano loop of Bill Evans’ “I Love You Porgy,” Mos pays homage to classic tracks like Eric B. & Rakim’s “I Know You Got Soul,” as he testifies to being consumed by his passion to create, chronicling how he first fell in love with the music during an era when few considered that hip-hop would have a lasting legacy.

“Speed Law” is one of the best songs that Mos ever recorded, a master-class in rhyme construction and flow, as he continuously drops an onslaught of quotables over sped-up samples of Big Brother and the Holding Company and Christine Perfect. “Black steel in the hour, assemble my skill form my power,” he raps. “My poems crush bones into powder; you mumble like a coward / I’m Mos Def, you need to speak louder!” As he spits his rapid-fire lines, he implores other emcees to “slow down” and be aware of their surroundings. He later warns wack emcees to be aware of their deficiencies, rapping, “Tell the feds, tell your girl, tell your mother / Conference call your wack crew and tell each other.”

“Ms. Fat Booty,” the album’s first single, solidified his well-earned reputation as an extremely capable storyteller. After a pair of “meet cutes” with the smoking hot Sharice (“ass so fat you could see it from the front”), he begins an increasingly physical relationship. He becomes more and more infatuated with the woman, only for her to keep him at a distance. The song illustrates the differences in expectations that can occur in a relationship, and how men can project their own desires onto the motivations of the objects of their affection. The production, handled by Ayatollah, is some of the best of the late ’90s era, as he expertly chops the obscure Aretha Franklin track “One Step Ahead.”

Mos mostly holds down the lengthy album on his own, rapping (or singing) by himself on nearly every track. But when Mos does utilize guests, the results are great. Mos teams up with Busta Rhymes on “Do It Now,” trading verses over bouncy keyboards on a beat produced by Mr. Khaliyl. “Know That” is a sinister string-driven Black Star reunion, featuring a fiery verse by Kweli. Kweli unleashes his fury upon wack emcees, rapping, “You make a mockery of what I represent properly / Yo, why you starting me? I take that shit straight to the artery / Intellectual property, I got the title and the deed / I pay for rent, with the tears and sweat and what I bleed / Emcees imitate the way we walk, the way we talk / You cats spit lyrical pork with no spiritual thought.”

One of Black On Both Sides’ central themes is the celebration of the area of Mos’ birth. Songs like “Brooklyn” provide a window into the city’s largest borough in all of its gritty, pre-gentrification glory, back when it would be unthinkable to walk to the corner of Putnam and Tompkins Ave. even in broad daylight. Mos splits the track into three separate “moves,” one produced by Ge-Ology and the other two produced by Mos himself, each with its own distinct feel and groove. And throughout the song, Mos makes it clear that the rough environment where he was raised doesn’t temper his affection for the place of his birth. “I love my city, sweet and gritty in land to outskirts,” he declares. “Nickname ‘Bucktown’ ’cause we prone to outburst.”

“Habitat,” produced by Etch-A-Sketch, covers similar ground, as Mos zeroes in on his personal experience growing up in the Bed-Stuy neighborhood. He explains attempting to find solace in the midst of the chaos that could consume his neighborhood, seeing himself as a “pirate on an island seeking treasure known as silence.” He delves into the predatory nature of bullies in his neighborhood and their desire to “dominate the weaker on the street / Hungry bellies only love what they eat and it's hard to compete / When they smile with your heart in they teeth /And the odds is stacked high beyond and beneath.”

Enjoying this article? Click/tap on the album covers to explore more about Mos Def/Yasiin Bey:

Mos was ahead of his time with “New World Water,” where he foretells of an impending fresh water shortage over a bubbly track produced by Psycho Les. Mos describes how the ravages of global warming and the wasteful nature of the wealthy are setting the stage for a time when the water supply will be completely privatized and “you be buying Evian just to take a fucking bath.”

Another clear highlight is the DJ Premier-produced “Mathematics.” Preemo crafts a suitably unorthodox beat to fit Mos’ extremely unorthodox style, chopping and re-splicing the guitar licks from Fatback Band’s “Baby, I’m-a Want Ya.” Mos shines on the track, painting vivid imagery while rapping “Power-lift the powerless up out of this towering inferno / My ink so hot it burn through the journal / I’m blacker than midnight on Broadway and Myrtle / Hip-Hop passed all your tall social hurdles.”

As mentioned earlier, Mos is a skilled singer, and some of the album’s most memorable entries don’t feature any rapping on his part. The most notable is “UMI Says,” the album’s second single, often known for its use in a commercial for Air Jordans. Mos “put[s] my heart and soul into this song,” reflecting on the importance of enjoying the moment because “tomorrow may never come.” Mos, who plays bass on the song, is joined by the late great jazz instrumentalist Weldon Irvine, who plays organ. Will.I.Am of the Black Eyed Peas also contributes, playing keyboard and helping give the song its unique groove.

Black On Both Sides was a hit critically and commercially. It was certified Gold, which was completely unheard of for an “underground” hip-hop album during the late ’90s. However, the future didn’t hold similar success for Mos. Five years later he would release The New Danger (2004), of which there are many passionate fans out there. I’m not one of them.

The New Danger was followed by a decade-and-a-half of malaise, where Mos only occasionally seemed to care about making music. While he released the masterpiece that was The Ecstatic (2009), too often he seemed to be putting in the least amount of effort required. This resulted in clunkers like Tru3 Magic (2006) and December 99th (2016).

But whatever slip-ups Mos may have made in the subsequent 20 years that followed BOBS, it doesn’t diminish the brilliance that’s often found on this album. It established that when swinging for the fences, Mos could launch a 550-foot dinger. With a potential upside like that, believing that Mos could reshape hip-hop in his own image didn’t seem that far-fetched.

LISTEN:

Editor's note: this anniversary tribute was originally published in 2019 and has since been edited for accuracy and timeliness.