Happy 50th Anniversary to Donny Hathaway’s final studio album Extension of a Man, originally released June 18, 1973.

Few soul artists in the 1970s evinced a musical lexicon and range as expansively as Donny Hathaway. He was a master musician, songwriter, arranger, and composer whose sophisticated synthesis of jazz, blues, gospel, funk, and classical influences bolstered a deeply spiritual brand of soul music. His eloquent taste in interpreting concepts he cerebrally contextualized and would later improvise upon in the studio and on stage was uniquely drawn from gospel and jazz traditions.

Within every melody, arrangement, and chord was his knack in stretching beyond form and convention. Counteracting what he gathered about the lineage of black music and its contentious relationship with American music forms, Hathaway furthered the possibilities of his musical expression and technicality as a means of not restricting himself, or being pigeonholed by a particular style. For him, music, in every facet, was the pure embodiment of our times and existence.

“When I think of music, I think of music in totality, complete, from the highest blues to the lowest symphony,” Hathaway revealed in an unidentified 1973 interview. “What I’d like to do is to exemplify each style of as many periods as I can possibly do.”

With one listen to his third and final studio album, 1973’s Extension of a Man, there’s little doubt that Hathaway was in the midst of an envelope-pushing space, deepening every fiber of his reach and groove. Even its hefty title suggests exacting ambition, as Hathaway implies in the album’s copious liner notes that he is “in the process of expanding and developing styles.” A year before, he scored the eclectic soundtrack to the blaxploitation film Come Back Charleston Blue (1972), brimming with many new stylistic turns.

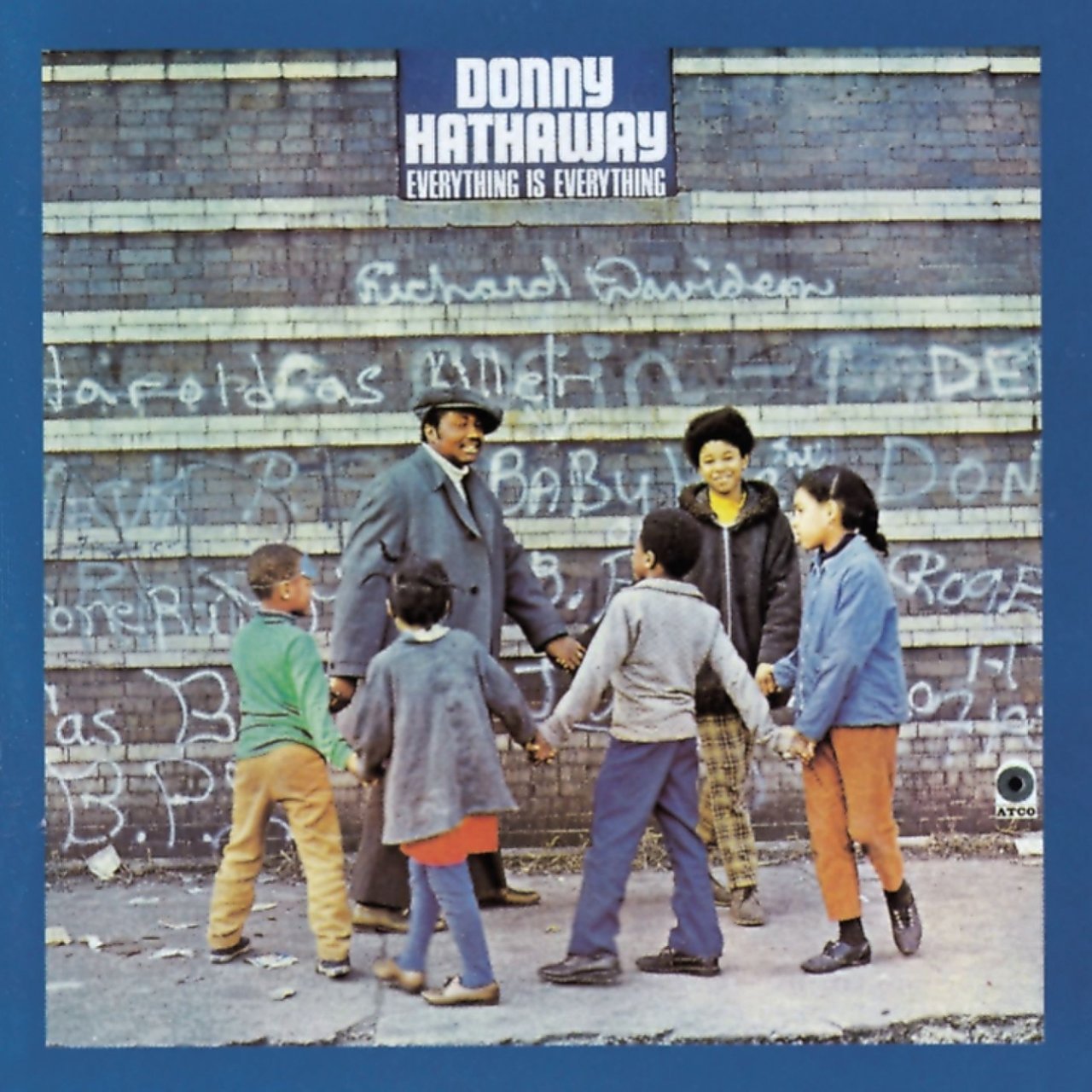

Where his first two epochal albums—1970’s Everything is Everything and 1971’s Donny Hathaway—capture the innate gospel impulses that were tremendous hallmarks in his ubiquitous sound, Extension broadens those sensibilities and luxuriantly welds them into a chameleonic canvas of stylistic variation and depth. The bold versatility presented throughout the album demonstrates Hathaway’s goal of widening the traditional modes of black music, while challenging its pioneers, tastemakers, and audiences to move it into foreign, explorative spaces.

Very often, Hathaway studied the work of renowned classical composers, such as Maurice Revel, Claude Debussy, Ivor Stravinsky, Sergei Rachmaninoff, and George Gershwin. He also cited them as primary influences of what he aspired to muster as a black composer. Reaching boundless extremes most mainstream soul albums of its era or since then haven’t dared to venture, Extension opens with an orchestral overture, “I Love the Lord; He Heard My Cry (Parts I & II).” Masterful in its execution and uncharacteristically cinematic in nature, “Lord” is a spiritual tone poem with deep religious undertones (hence the title and the hymn it’s inspired by). It also showcases Hathaway’s stunning prowess as a composer and arranger, melding impressionistic tonalities with emotional timbres from the Romantic period.

Listen to the Album:

As the piece’s dramatic first movement builds its cyclical grandiosity, elaborate electric piano stabs spring into the center. The otherworldly harmonies of Myrna Summers & the Interdenominational Singers add a humanly touch to the swirling orchestrations as well. When it all dwells into its second movement, Hathaway punctuates a stately 5/4 meter beat that spruces up the piece with jazzy flair. Then, everything calmly descends and segues eloquently into “Someday We’ll All Be Free.”

Gliding gently over a bed of dreamy electric piano sprinkles and a delicate acoustic guitar, “Someday We’ll All Be Free” declares its poignancy right from the start. Conceived as an inspirational ballad to help alleviate Hathaway’s increasing bouts with depression, the song’s lyricist and Hathaway’s friend Edward Howard first caught wind of it after Hathaway played him a sketch of the song and asked him to write lyrics for it. Initially unable to spark any ideas, Howard was mysteriously inspired to write the song after almost falling in a shower. The pensive nature of the lyrics is awfully heartbreaking, as if Hathaway is salvaging himself from his own troubled consciousness: “Keep your self-respect, your manly pride / Get yourself in gear / Keep your stride / Never mind your fears / Brighter days will soon be here.” While hearing a playback of the song’s final mix, Hathaway was reportedly moved to tears by not only the song’s message, but its stirring arrangement.

Since Hathaway’s original rendering, “Someday We’ll All Be Free” has been recognized as a classic anthem of empowerment and freedom in the black community. Interestingly enough, Hathaway casually described it as “a tune of ‘standard’ quality,” in his notes for Extension. It has also been covered by several artists over the years, with its most famous reinterpretation coming from none other than Aretha Franklin, who recorded it in 1992 for Spike Lee’s epic biographical film Malcolm X.

In 1969, Hathaway cut a largely forgettable instrumental version of “Flying Easy” with the Woody Herman Band on Chess Records, in hopes that it would generate buzz from United Airlines to utilize it in a national advertising campaign. According to Hathaway’s notes for Extension, he originally wrote the composition for Herb Alpert & the Tijuana Brass. Some odd years later, Hathaway revisited the song with its original lyrics written by Walter Lowe and Franklin Moss, Jr. for Extension.

Boasting a light, easy listening pop approach that skirts on bossa nova, “Flying Easy” shines with sun-soaked buoyancy and positive affirmation. If one were to daringly place the song’s lyrics in the context of the era Hathaway’s version was recorded, it could be argued that the upward theme ironically correlates to the emergence of social and economic advancement for the black middle class of the mid-1970s.

Swimming deeper into the jazz realm, the free-flowing instrumental “Valdez in the Country” beautifully circles around a strong Latin-rock influence. Anchored by Hathaway’s skillful electric piano work and intriguing chord changes, the instrumental features energetic interplay from the rhythm section, with the incomparable Willie Weeks on bass and Ray Lucas on drums. Flaunting his fluent blues vocabulary, Hathaway mightily tackles Blood, Sweat & Tears’ classic “I Love You More Than You’ll Ever Know” with total abandon and heartfelt passion in his sultry, gospel-drenched delivery.

Hathaway manages to center in on adolescence and community with the streetwise funk ditty, “Come Little Children.” The nursery rhyme-laden flair of the song was born out of the ebullience of his childhood and the outdoor games he would actively be involved in with other children. Impressively, the brass arrangements utilize a playful refrain from the Miles Davis evergreen, “All Blues.”

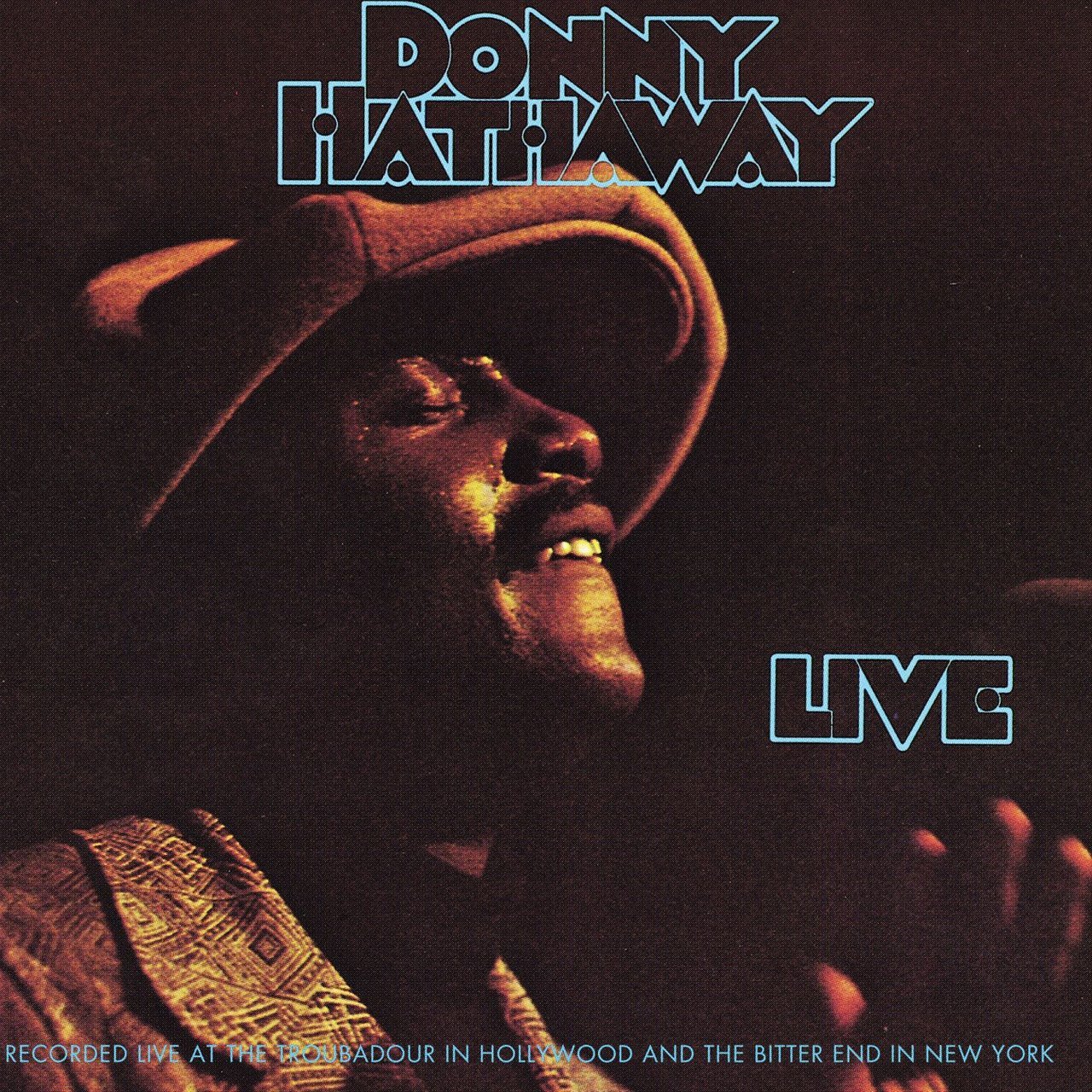

Enjoying this article? Click/tap on the album covers to explore more about Donny Hathaway:

It would come as no surprise if Hathaway was heavily affected by the nuances of Marvin Gaye’s 1971 masterpiece What’s Going On. In fact, he often covered the prophetic title song during many of his live dates, shortly after Gaye released it as a single in January 1971. Likening its arrangement and rhythm to much of Gaye’s soul-jazz inflected grooves throughout What’s Going On, “Love, Love, Love” finds Hathaway flexing his romantic side, with a strong smooth soul atmosphere that places slick pop-soul delicacies of Motown alongside subtle slices of Philadelphia soul.

When Hathaway recorded “The Ghetto” in 1969, he ruminated on the dark philosophies and gritty ambiances of inner-city life. He seemingly revisits this gesture on “The Slums,” which he personally coined as an optimistic, upbeat answer to “The Ghetto.” Just as “The Ghetto” emphasized a smoky, jazz-soul style that centered on Hathaway’s effortless knack for improvisation, the funk-based “The Slums” treads similar territory, with a more direct emphasis on brass and rhythm section solos.

Pushing the eclecticism into more unfamiliar avenues, Hathaway’s cover of Danny O’Keefe’s darkly humorous ode to a brothel legend, “Magdalena,” flirts with rootsy Americana idioms as well as melodic blues underpinnings that he seemed well versed to infuse in much of his work.

The Leon Ware-written ballad “I Know It’s You” caps the album on a deeply earnest note, marveling on the beauty of domestic and spiritual love. According to Extension’s liner notes, the song was suggested to Hathaway by the late great Jerry Wexler, who was Atlantic Records’ executive vice-president at the time. Lushly arranged by the legendary Arif Mardin with a young Stanley Clarke showcasing his exceptional bass chops, the slow soul ballad sports Hathaway’s soulfully expressive voice and a knockout chorus of “No, I ain’t got / Nobody else in mind / I know it’s you.”

Upon its initial release in the summer of 1973, the wildly eclectic Extension of a Man didn’t exactly attract the same audiences that favored his previous solo work or his collaborative work with Roberta Flack. It didn’t do well commercially either. Executives at Atlantic Records were often confounded by marketing his magnificently varied music; his artistry couldn’t be straitjacketed to a particular style or form.

It must also be noted that Hathaway’s mental imbalances were becoming increasingly worse by the time he recorded this album. A thick air of gravitas pervades much of Extension not just because of its surrounding circumstances, or the fact that it sadly became his final album before his untimely death in 1979.

It’s the monumental work of a rare genius, exploring intensely beyond convention, while peaking at his own expense. If it all sounds overreaching, it was intentional. Hathaway had an abundance of talent with ambition to spare. He allowed it to unfurl in one massive sprawl. Just as legendary poet Nikki Giovanni scribed in her exquisite, long-form meditation for the album’s liner notes: “A man extends himself when he shares his dreams; and we extend ourselves when we receive them.” Extend on.

LISTEN:

Editor's note: this anniversary tribute was originally published in 2018 and has since been edited for accuracy and timeliness.