Happy 50th Anniversary to Isaac Hayes’ fifth studio album Black Moses, originally released in November 1971.

Staring at our screens, clicking or tapping to consume our music, it barely registers that albums even have covers anymore. That tiny square of color pales in comparison to the glorious works of art that adorned album covers from the 1950’s onwards. But that’s progress, right?

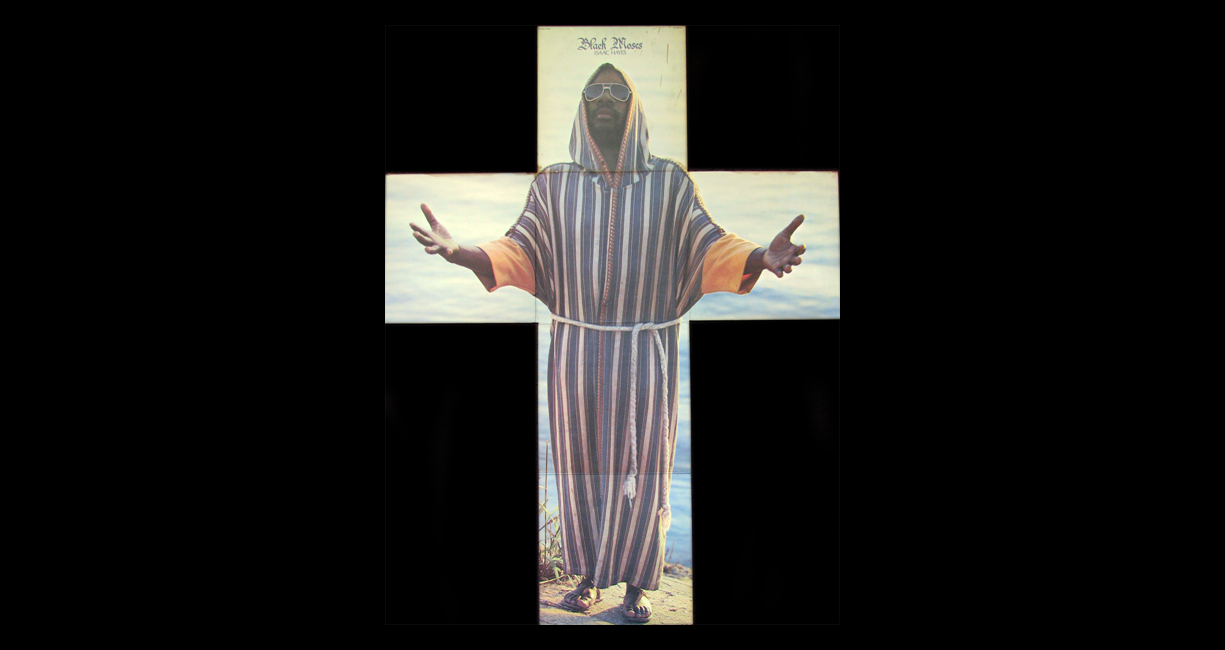

They certainly pale in comparison to Isaac Hayes’ 1971 album Black Moses, which goes down as one of the most outrageously flamboyant record covers ever issued—a folding monolith that revealed a four foot by three foot crucifix that showed Hayes clad in regal, righteous Nubian robes. The cynic in us suggests that the existence of such an elaborate construction must be to hide the poor quality of the work on offer and indeed Larry Shaw (Stax’s advertising and packaging chief) felt the same. His feelings were recounted in Robert Gordon’s definitive Respect Yourself: Stax Records and the Soul Explosion when he insisted, “The music in there was of such a poor quality, we had to sell the box it came in.”

Even the title itself proved slightly problematic for Hayes. As a proud, fallible but God-fearing man he felt immediately uncomfortable with the epithet given to him by promo man Dino Woodard one night at the Apollo Theater, but it soon gathered momentum and got picked up by Jet magazine and others. Such was his standing in the Black community and the overwhelming effect of his performances on the audience, it seemed a fitting, if vaguely sacrilegious, name.

So to understand Black Moses you need to delve into the context of both Stax Records and Isaac Hayes, so intertwined were their histories and destinies. Hot Buttered Soul had blown minds at Stax (and beyond) in 1969 and given them a new MVP after the untimely death of Otis Redding. Hayes’ dramatic re-interpretations of others’ songs, his own startling new compositions and booming bass proto-raps were unlike anything anyone had heard before.

1971 brought the iconic, genre-defining and Oscar-winning soundtrack to Shaft. So it was somewhat of a shock that even as Stax squeezed the last pips out of Shaft, another album duly landed at their feet, courtesy of its creator. That it was a double album of 14 songs, clocking in at over 90 minutes simply added to the feeling of quantity over quality. In reality though, Hayes was simply continuing in the same vein as he always had—along with Booker T and the MGs, he had contributed to more records than anyone else at Stax. Just as the Funk Brothers drove Motown, so they drove Stax.

Of course looking back from this point, it is occasionally hard to take this record at face value. The sexual loverman prowl of his raps. The wah-wah guitar and the cinematic soul arrangements have been parodied countless times and bastardized by the co-opting of its sound in commercials and the like. But by persevering it is possible to see past all of this and embrace its originality and ambitious scope.

Of the 14 songs here, the majority are covers and the great joy of an Isaac Hayes cover is the way in which he deconstructs, rearranges, and reassembles songs that seem so un-Hayes like. Take his version of “(They Long to Be) Close to You” by the Carpenters. Playing it totally straight, Hayes’ profundo bass is simultaneously totally alien and utterly compelling. Reimagining the sickly sweet, easy listening hit as an orchestral funk opus took some doing, but Hayes did it with aplomb.

Cherry picking songs by peers such as Curtis Mayfield (“Man’s Temptations”), Gamble and Huff (“Never Gonna Give You Up”), and Kris Kristofferson (“For the Good Times”) ensured the lengthy running time had legs—the quality of penmanship allied to the inventive re-workings and Hayes’ own compositions meant two months at the top of the RnB chart. The album’s lead single—the cover of the Jackson 5’s “Never Can Say Goodbye”—reached number 22 on the pop charts and went top 5 in the R&B, all of which meant that 1971 was a stellar year for both Hayes and Stax, so much so that early the following year, he was nominated for seven GRAMMY awards.

Being at such a creative and commercial peak meant that it was a prime time for Hayes to negotiate a new contract. But at this crucial juncture Hayes would unwittingly contribute to the demise of the label he had been a founding rock of. In order to keep the hit machine that Hayes had become going, Stax head honcho Al Bell’s sweeteners became more and more outlandish and less and less sensible. After all, what’s a $26,000 gold plated Cadillac between friends? The house that Hayes had helped to build had become huge, unwieldy and hemorrhaged money—without a better business sense it would eventually come to nought.

Yet on revisiting Black Moses, the heady atmospherics are the things that strike home. “Ike’s Rap II” —sampled so memorably by Portishead for “Glory Box” from their 1994 debut album Dummy—is the perfect example of why Larry Shaw was so wrong. The woozy bassline, the melancholic strings and the intimacy of Hayes’ half-whispered musings are a seductive and beguiling concoction. And ultimately, this is precisely what will be remembered in years to come—the ground-breaking genius of Isaac Hayes’ 1971 pinnacle.

LISTEN:

Editor's note: this anniversary tribute was originally published in 2016 and has since been edited for accuracy and timeliness.