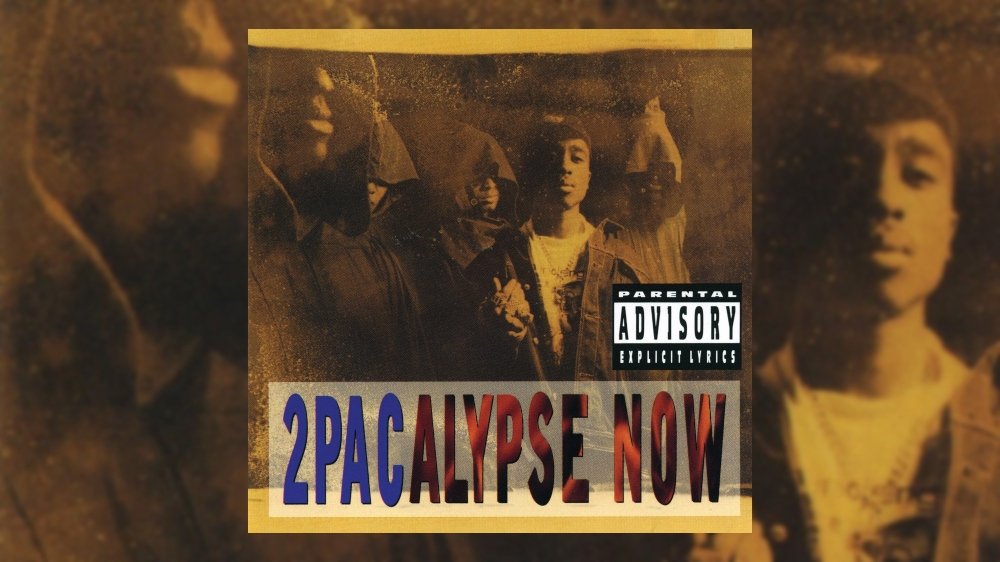

Happy 30th Anniversary to 2Pac’s debut album 2Pacalypse Now, originally released November 12, 1991.

When I think of 2Pac’s music, my fondest memories invariably gravitate toward his pre-Death Row Records period and more specifically, the few years immediately following his stint in the vibrant and vivacious Oakland hip-hop collective Digital Underground.

Though his mega-stardom was cemented with the latter three of his five studio albums (1995’s Me Against The World, 1996’s double-album All Eyez On Me, and 1996’s The Don Killuminati: The 7 Day Theory posthumously released under his pseudonym Makaveli), I still consider his first two LPs (1991’s 2Pacalypse Now and 1993’s Strictly 4 My N.I.G.G.A.Z.) to be his most memorable and powerful. There was arguably something purer about these earlier recordings, unfettered by the influence and oversight of Suge Knight’s infamous empire.

Tupac Amaru Shakur first garnered modest attention within hip-hop circles upon the late Shock G inviting him to “go ‘head and rock this” on Digital Underground’s 1991 single “Same Song,” which appeared on both the soundtrack to the instantly forgettable 1991 film Nothing But Trouble and subsequently the group’s This Is An EP Release, the follow-up to their classic 1990 debut album Sex Packets. As his career progressed shortly thereafter, the self-proclaimed “Rebel of the Underground” functioned as a more controversial and provocative counterweight to the farcical shtick of Shock G’s entertaining split personality, Humpty Hump.

1991 proved to be a watershed year for Shakur. While recording sessions for his debut album 2Pacalypse Now had commenced two years earlier in 1989, he and his crop of producers spent the year placing the finishing touches on the song suite in anticipation of its November release. In parallel, Shakur also made brief cameos on “The DFLO Shuffle” and “Good Thing We’re Rappin’” from Digital Underground’s sophomore LP Sons Of The P, which arrived four weeks before 2Pacalypse Now. He also completed his first-ever acting role on the silver screen, playing the volatile Roland Bishop in Ernest R. Dickerson’s excellent film Juice, which hit theaters in January 1992.

But while 2Pacalypse Now emerged just as Shakur’s cross-media career was taking flight, the timing of its release was arguably even more notable with respect to the broader social and cultural context of what was transpiring across America at the time.

Eight months earlier, an eyewitness’ amateur video had captured four white LAPD police officers savagely beating African American motorist Rodney King to a bloody pulp after a high-speed car chase. And while videos like this have become commonplace 30 years later, the emergence of the King video back in March 1991 raised the collective ire of millions of Americans who had not understood—or had naively refused to accept—the reality and long legacy of racially-motivated police brutality, until they were able to observe it with their own eyes.

Nearly fifteen months passed before the four officers were acquitted of all charges of assault with a deadly weapon and use of excessive force (two of the officers were subsequently found guilty of the latter charge and sentenced to 32 months in prison by a federal grand jury in March 1993). In the acquittal’s immediate aftermath, the tension-filled powder keg of Los Angeles erupted in six days of rioting marked by widespread violence, burning, and looting.

Although Shakur never could have foreseen precisely how these circumstances would ultimately unfurl, his thematic focus and lyrical disposition across 2Pacalypse Now certainly augured much of what was invariably to come. Across the 13-song battle cry, he rages and rhymes against the machine, examining the various seeds and manifestations of the institutionalized suppression of the Black community in America. In the provocative “Words Of Wisdom,” he rhetorically wonders why his Black brethren should ever “Pledge allegiance to a flag that neglects us.”

Largely fueled by his own experiences and observations, Shakur’s debut is a sobering yet vivid portrait of the Black experience in America and a seething diatribe against the persistent plague of racial inequality and injustice. “I'm still down for the young Black male,” 2Pac explained to hip-hop journalist and media activist Davey D in 1991. “I'm gonna stay until things get better. So [2Pacalypse Now] is all about addressing the problems that we face in everyday society. Police brutality, poverty, unemployment, insufficient education, disunity and violence, black on black crime, teenage pregnancy, crack addiction.” Regrettably, many of Shakur’s insights and laments are just as relevant today, if not more so, then they were three decades ago.

Though 2Pacalypse Now remains the least commercially successful and arguably most obscure album—relatively speaking, that is—among Shakur’s five studio LPs, in the case of one track in particular, it did manage to garner prominent attention on a national scale.

Over a sample of Bill Withers’ 1971 classic “Ain’t No Sunshine,” the two-part narrative “Soulja’s Story” finds Shakur delivering foreboding, slow-motion rhymes that examine the psychological, and all-too-often tragic, toll of being Black and persecuted in America. The first verse presents a fictional account of a young Black man exacting retribution for his marginalized place in society by shooting a police officer (“Is it my fault, just cause I'm a young black male? / Cops sweat me as if my destiny is makin' crack sales / Only fifteen and got problems / Cops on my tail, so I bail 'til I dodge 'em / They finally pull me over and I laugh / ‘Remember Rodney King?’ and I blast on his punk ass”). The second verse revisits the story of imprisoned Black Panther and Soledad Brother George Jackson, and more specifically the botched jailbreak staged by his brother Jonathan in a Marin County courthouse in August 1970.

Five months after 2Pacalypse Now’s release, the song was enmeshed in controversy, causing some cultural pundits and political leaders to blur the lines between fact and fiction, life and art. In April 1992, Ronald Ray Howard shot Texas state trooper Bill Davidson after the latter pulled him over for driving a stolen vehicle. Davidson died from his injuries three days later. As part of his defense, Howard’s attorney claimed that his client had been listening to “Soulja’s Story” when he was pulled over by Davidson, and the content of the song influenced his decision to shoot. The lawyer’s misguided and opportunistic attempt to scapegoat Shakur and, more broadly, his hardcore/gangsta rap brethren ultimately failed to sway the jury. Howard was convicted of capital murder and sentenced to death, which was carried out through lethal injection in October 2005.

As a result of the defense’s strategy, however, plenty of conservative political figures expressed their opposition toward “Soulja’s Story,” with then Vice President Dan Quayle most notably opining, “There’s no reason for a record like this to be released. It has no place in our society.” The antagonism would soon extend to prominent African American leaders as well, including Reverend Jesse Jackson and C. Delores Tucker, who denounced what they perceived to be violent and misogynistic lyrics in Shakur’s and other rappers’ songs. Obviously, as evidenced by the continued ascension of hip-hop music throughout the ‘90s into the new millennium, the criticism didn’t inhibit Pac and his peers from continuing to exercise their first amendment rights.

While “Soulja’s Story” was singled out by many due to the infamous Howard case, there are plenty of songs on 2Pacalypse Now that showcase Shakur’s penchant for provocation and incisive social commentary. Following the conspicuously irreverent “fuck all y’all” tone and admittedly unpolished lyrics of album-opener “Young Black Male” (which also re-surface three songs later on the appropriately titled throwaway tune “I Don’t Give a Fuck”), the first of the handful of standout tracks surfaces.

Lead single “Trapped” is a stark yet cogently conveyed portrait of the reality and hopelessness of growing up Black, marginalized and confined to the ghetto, where few opportunities exist to transcend poverty, crime, and exploitation at the hands of the powers that be. For Shakur, music always represented the path out of the abyss, as he confides that “…I said I had enough / There must be another route, way out / To money and fame, I changed my name / And played a different game / Tired of being trapped in this vicious cycle / If one more cop harasses me I just might go psycho.”

Produced by Shakur’s Digital Underground comrades DJ Fuze and Money B, who recorded two underappreciated albums under the Raw Fusion moniker, the Reggae/Dub-tinged “Violent” proves one of the strongest examples of Shakur’s evolving lyricism, as best evidenced by the latter half of the first verse: “I'm Never Ignorant, Getting Goals Accomplished / The Underground Railroad on an uprise / This time the truth's gettin' told, heard enough lies / I told 'em fight back, attack on society / If this is violence, then violent's what I gotta be / If you investigate you'll find out where it's comin' from / Look through our history, America's the violent one / Unlock my brain, break the chains of your misery / This time the payback for evil shit you did to me / They call me militant, racist cause I will resist / You wanna censor somethin,’ motherfucker censor this! / My words are weapons and I'm steppin' to the silent / Wakin' up the masses, but you, claim that I'm violent.”

Two additional tracks were officially released as singles and they’re both unequivocal highlights. On the heartfelt, nostalgia-fueled “If My Homie Calls,” which samples Herbie Hancock’s “Fat Mama” to head-nodding effect, Shakur vows eternal loyalty to his childhood best friend, admitting that despite the fact that he’s “livin’ kinda swell now” due to his newfound fame, he’ll always be there if his homie needs him.

The album’s emotional weight is arguably most pronounced on the sobering “Brenda’s Got A Baby,” which explores the adversity and isolation of teenage pregnancy (and in the case of the fictional Brenda, pre-teen pregnancy) spawned from a broken home. Also notable is the trio of tracks produced by Shock G (“Words of Wisdom,” “Tha’ Lunatic,” “Rebel of the Underground”), all of which embrace DU’s signature funk-blessed soundscapes.

When I first heard 2Pacalypse Now in the fall of 1991, I, and no one for that matter, could have ever envisaged that its creator would die less than five years later at the young age of 25. We also couldn’t have fathomed how high his legend would ascend in such an abbreviated time.

Regardless of how you might feel about how his complex and sometimes contradictory messages evolved across his short-lived career, it’s damn near impossible to deny that 2Pac was and will forever be revered as one of the most vital and influential emcees in hip-hop history. And for the new generation of hip-hop heads who weren’t alive and kicking yet to see and hear 2Pac in the flesh, you’d be well advised to consult his contemporary heir-apparent Kendrick Lamar for a brief history lesson.

LISTEN:

Editor's note: this anniversary tribute was originally published in 2016 and has since been edited for accuracy and timeliness.