Happy 25th Anniversary to Over the Rhine’s Good Dog Bad Dog: The Home Recordings, originally released June 30, 1996.

I’ve written quite a few album tributes in my day. Each of the recordings I’ve revisited and celebrated over the years holds special meaning for me. And when warranted, I’ve embedded my own anecdotes and sentiments within these lines, to balance my more objective critical eye with my unapologetically biased perspective about, and personal history with, the albums I adore.

My love for Over the Rhine’s Good Dog Bad Dog: The Home Recordings runs deep. Far deeper than most of the albums I’ve written about to date. Twenty-five years since I heard it for the first time, it still thrills me and instantly restores my faith in the power of music each time I press play. The sublime, soul-affirming songs contained therein have much to do with it, of course. But the circumstances that led me to discover the album in the first place also play a huge part in my unconditional and eternal affection for Good Dog Bad Dog, not to mention the band’s entire recorded repertoire.

Back in the summer of 1998, between my junior and senior years at UCLA, I interned at Geffen Records’ Sunset Boulevard offices in Hollywood. Geffen, best known for galvanizing the careers of Guns N’ Roses and Nirvana, boasted a stellar artist roster at the time, which included the likes of Beck, Hole, and Sonic Youth, plus Elliott Smith and Rufus Wainwright via their distribution deal with DreamWorks Records. But the Geffen band that I was most excited about was Cowboy Junkies, who I had faithfully listened to since they released their masterful 1988 sophomore LP The Trinity Session.

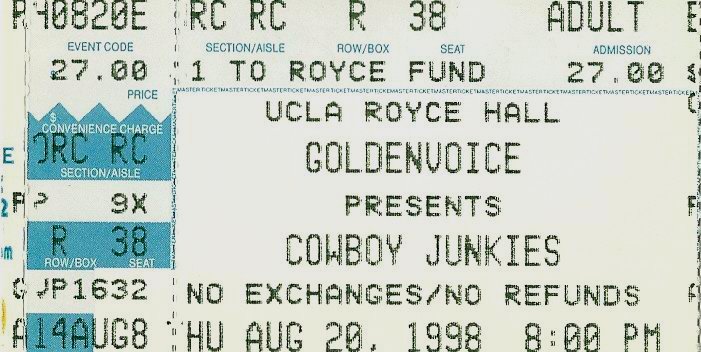

I vividly recall being quite chuffed when I was handed a pair of tickets to the Junkies’ August 20th show at Royce Hall, the most iconic building on my alma mater’s campus. Their performance was nothing short of stunning, but it was the opening act whom I had never heard of before that completely shook my soul.

I was absolutely riveted by Over the Rhine’s songs, largely culled from Good Dog Bad Dog. More specifically, I was stupefied by Karin Bergquist’s soaring, pitch-perfect voice that sent chills up and down my spine multiple times during their short set. Halfway through their performance, I remember leaning over toward my friend Vanessa, and whispering in her ear, “Who are they, and how have I lived this long without them in my life?”

Witnessing Over the Rhine on stage that evening was an unanticipated revelation, an epiphanic experience that I still vividly replay in my mind from time to time. I was so instantly enamored with their music that, as if by some gravitational pull emanating from their merch table, I compulsively sprung from my seat after their final song and proceeded to hand over a small sum for the Good Dog Bad Dog CD.

For the next few months, I played the album often and loud in my Westwood apartment, the songs’ melodies flooding the building’s courtyard. So loud, in fact, that my next door neighbor, an aspiring singer and dancer with a rather lovely voice, overheard it one evening, knocked on my door, and demanded to borrow the CD for the evening. A few days later, and for weeks afterward, I could hear her belting out “Latter Days,” “Faithfully Dangerous,” and “Poughkeepsie,” which once again reinforced the powerful allure of Over the Rhine’s exquisitely crafted songs. One listen, and you’re hooked.

Bergquist and Linford Detweiler, who met while studying at Malone University in Canton and later married in the fall of 1996, formed Over the Rhine in the spring of 1989 in the Cincinnati neighborhood of the same name. The duo became a quartet when guitarist Ric Hordinski and drummer Brian Kelley joined the fold, and they released their first two albums, Till We Have Faces (1991) and Patience (1992), independently under their Scampering Songs moniker.

Shortly after the release of Patience, and on the undeniable strength of their first two batches of songs, Over the Rhine signed with I.R.S. Records. At the time, the independent label boasted a distribution deal with EMI and a storied history developing the careers of Concrete Blonde, The Go-Go’s, and R.E.M., among many others. After a 17-year run, which included reissuing Till We Have Faces and Patience as well as releasing Over the Rhine’s third LP Eve (1994), I.R.S. shut its doors in early 1996, and Bergquist, Detweiler, and crew were relieved of their recording contract as a result. In Good Dog Bad Dog’s liner notes, Detweiler wrote that he “was relieved to be free to go back home and make a new start.”

However, essentially back at square one professionally, their path toward this new start wasn’t immediately clear. “I was going through a phase when I was seriously considering packing it in as far as writing songs,” Detweiler confided to The Spokesman-Review in 2000. “I loved music, but we had worked really hard for four or five years prior to making [Good Dog Bad Dog]. Even though there were some beautiful splashes of color that come into the picture, we were pretty exhausted.”

The group’s newfound independence and their aforementioned love of making music ultimately compelled them to return to the DIY recording approach they originally embraced earlier in their career. Bergquist and Detweiler set to work on developing a new suite of songs in the familiar confines of the latter’s home, and the resulting “homespun pieces of reality” were woven together to form the band’s fourth album, Good Dog Bad Dog.

A crystalline collection of redemptive reveries, Good Dog Bad Dog is fueled by Bergquist and Detweiler’s empathetic examination of life’s duality in its many forms, as its title suggests. Across the album’s thirteen songs, the duo eloquently traverse the universal, fundamental human dichotomies between happiness and pain, hope and despair, love and loss, the saintly and the sinful—the recognition and reconciliation of which ultimately empowers us to lead fulfilling lives while enriching the lives of those who surround us. There are unmistakably spiritual allusions throughout, but the duo’s themes and words are never overtly religious, which allows the listener the freedom of interpretation based on how the songs happen to resonate with him or her.

The minimalist, piano-driven album opener “Latter Days” is indeed “a beautiful piece of heartache,” as Bergquist’s enthralling, emotive vocals acknowledge the disappointment inherent within life’s vicissitudes, with all-too-relatable references to “healthy apathy,” “broken dreams,” and “sleepin’ on a bed of nails.”

A more hopeful tone begins to emerge on “All I Need is Everything,” a yearning, guitar-driven ode to seeking truth and finding salvation, which reinforces Over the Rhine’s unparalleled penchant for deriving power in the plaintive. The notion of conquering, or at least enduring, one’s fear and pain resurfaces later on the gorgeous, gospel-tinged “Poughkeepsie,” with Bergquist proclaiming “No more drowning in my sorrow / no more drowning in my fright / I’d just ride on the backs of the angels tonight.”

The somber turned sanguine ballad “Etcetera Whatever” reminds us that love, beyond all else, offers the most reliable form of solace in our times of need. One can’t help but be moved by Bergquist’s earnest reassurances, as she sings, “We don’t need a lot of money. / We’ll be sleeping on the beach, / keeping oceans within reach. / (Whatever private oceans we can conjure up for free.) / I will stumble there with you / and you’ll be laughing close with me, / trying not to make a scene / etcetera. Whatever. I guess all I really mean / is we’re gonna be alright.” One listen to her repeated refrain of “Yeah, we’re gonna be alright. / You can close your eyes tonight, / ‘cause we’re gonna be alright,” and you too will feel the weight of your world start to lift.

Seizing life’s simple pleasures and finding strength within the intimacy of another are the key lessons shared on a trio of uplifting love songs that include the shimmering melody of “The Seahorse,” country-flavored flourishes of “Go Down Easy,” and swirling swagger of “Faithfully Dangerous.” With unforgettable, poetic lines like “Dip your hands in colors / while the young night flutters in on you / and finger paint me pictures of all you see,” the latter serenade is a must-listen for any couple wishing to ensure that their collective flame never flickers.

Other highlights include the contemplative “Everyman’s Daughter,” in which Bergquist considers her place within the broader context of humanity, the slinky groove of “Jack’s Valentine” featuring a rare spoken word contribution by Detweiler, the stripped-down “Happy to Be So,” and pair of instrumental tracks, the abbreviated “I Will Not Eat the Darkness” andthe Hordinski-led “Willoughby.”

Nearly two-and-a-half decades have now passed since I first witnessed Over the Rhine on stage that summer evening at Royce Hall and fell madly in love with Good Dog Bad Dog. A quarter-century on, I’m still awestruck by their musical integrity, humility and grace, and they remain one of the few artists that I support fervently and unconditionally.

I’ve seen Over the Rhine perform at least a dozen more times in Los Angeles, San Francisco, and New York City, my current home base. Their prolific discography occupies a permanent and revered place within my family’s record collection. “I Want You to Be My Love,” the opening song on Drunkard’s Prayer (2005), figured prominently in my wedding nearly twelve years ago. And while my wife stayed at home to care for our firstborn daughter during her first year, she played Meet Me at the Edge of the World (2013) more incessantly than any other record. No great surprise then that our daughter—now the eldest of our two—perks up whenever she hears Bergquist’s voice emanating from the speakers. Well, who wouldn’t?

While each of Over the Rhine’s albums possesses its own unique and irresistible charms, Good Dog Bad Dog will forever be the most inspired, the most vital, the most indispensable. Once referred to as the “little record that could,” for me, it’s the big record that always has and always will.

LISTEN:

Editor's note: this anniversary tribute was originally published in 2016 and has since been edited for accuracy and timeliness.